The feats of Will Scotland and his Caudron biplane - Blue Bird

New Zealand's first cross-country flight

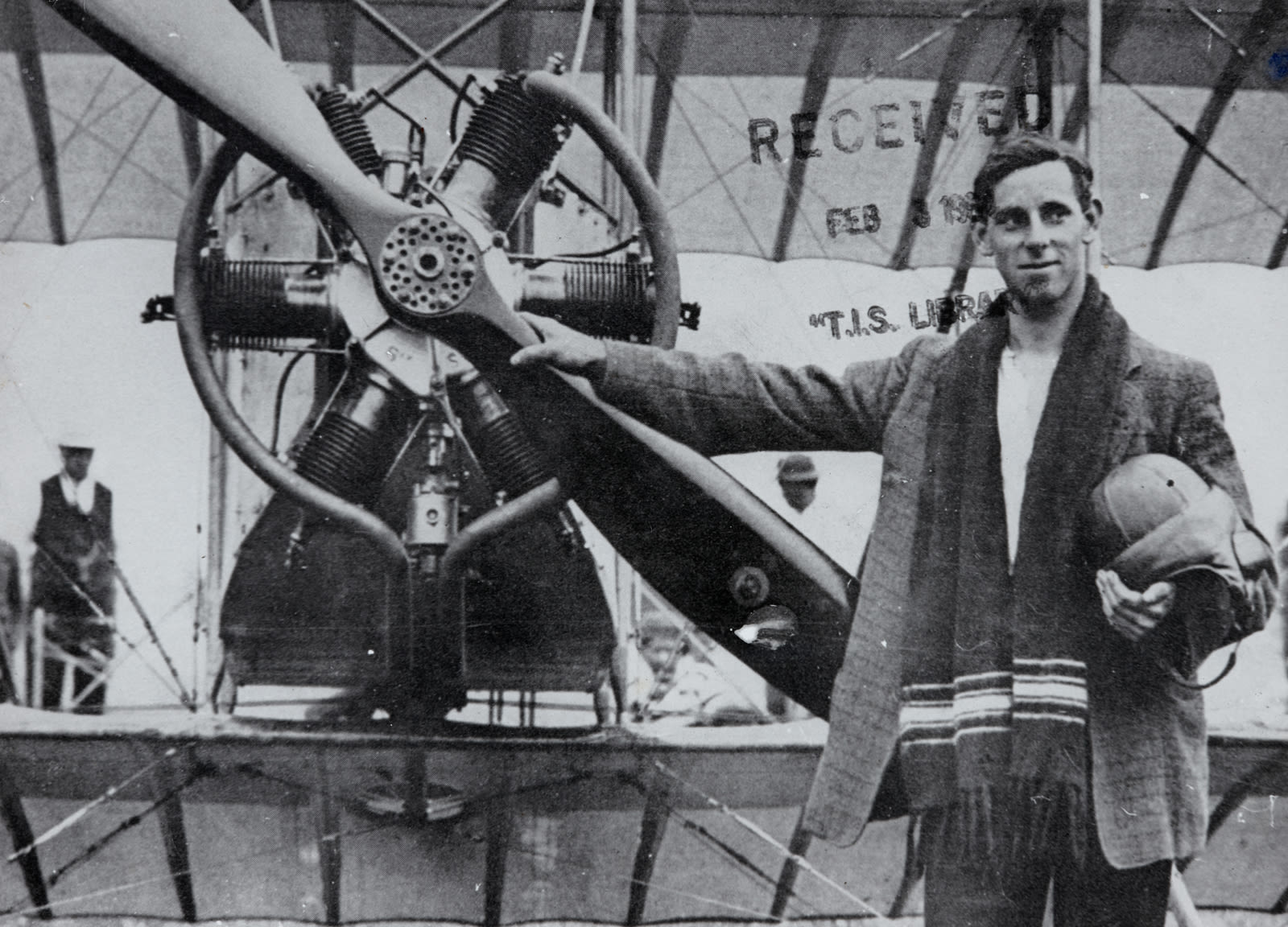

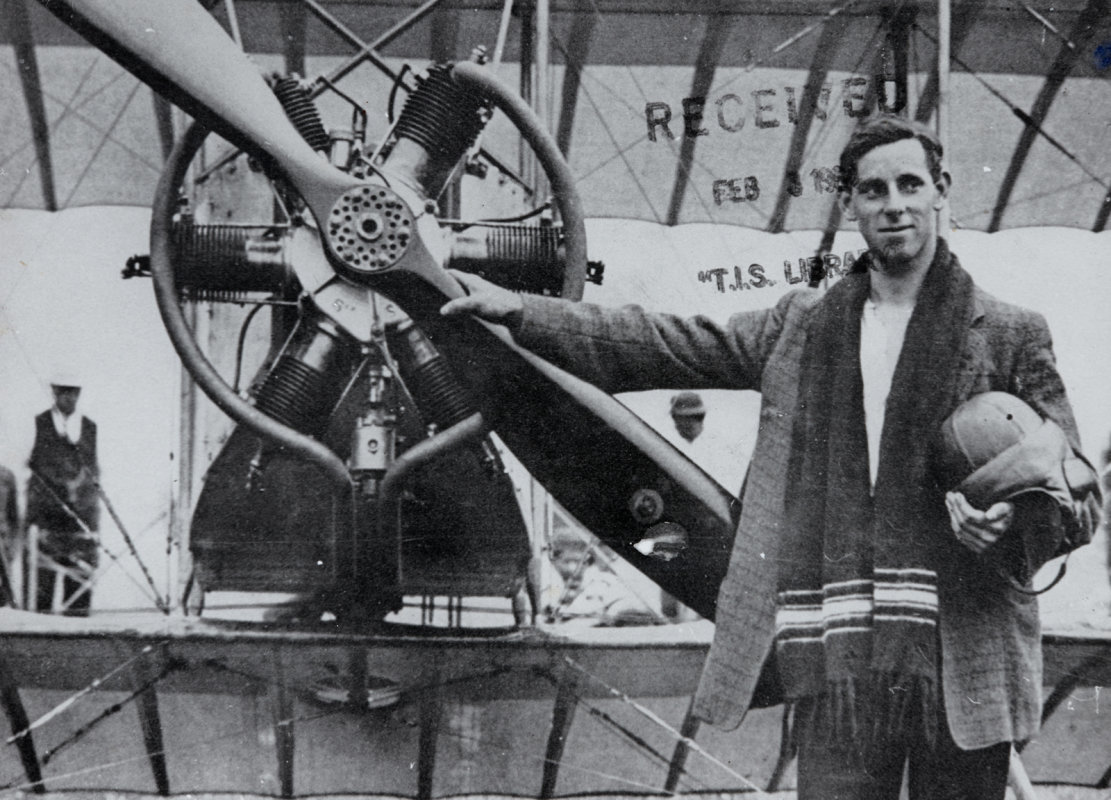

The J.W.H. Scotland collection housed at MOTAT, contains photographs, ephemera and the ‘Scotland medal’ – an inscribed medal commemorating a flight in March 1914. Inscribed on the front are the initials ”J. W. H. S.”, while the back is inscribed with the message: "To J W H Scotland from admirers of his flying ability, Dunedin, March, 1914."

The medal was recorded in MOTAT’s collection during 1978, and the inscription refers to the exploits of James William Humphrys Scotland who flew his Caudron ‘C’ biplane, Blue Bird, from Invercargill to Gore in March 1914, completing the first cross-country flight in New Zealand. From Gore, he made his way north, stopping at Dunedin, then onto Timaru and Christchurch. From Christchurch, Scotland had planned to reach Wellington, but this came to an uncomfortable end on 25 March when he crash-landed on Wellington’s Newtown Park.

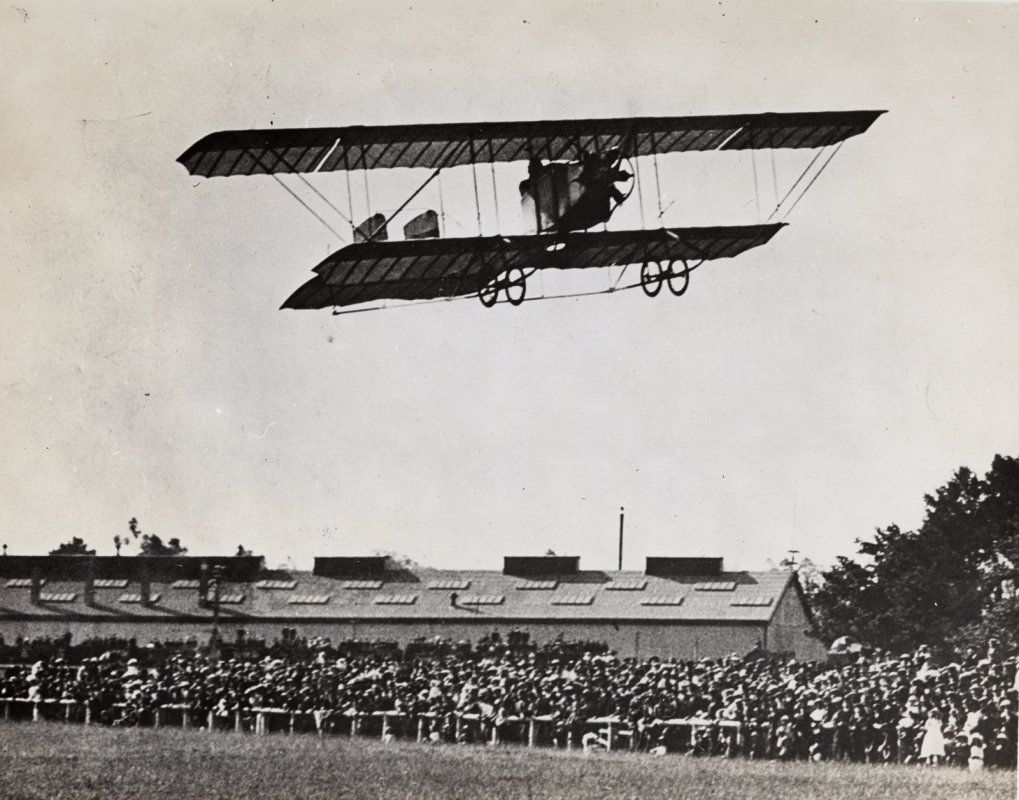

Also included in the collection are photographic postcards showing Scotland and the Caudron biplane, and photographs of Scotland with his Caudron, both in flight and on the ground, and of the wreckage of the Caudron in a tree in Newtown Park.

The Early Years

Scotland was born on 21 September 1891 at Pahi on the Kaipara Harbour. Will, as he was known, grew up in Pahi, but was sent to Auckland’s St. John's Collegiate School at “The Pah” in Onehunga. After leaving school he became an apprentice to a chemist in Karangahape Road, but travelled to England at age 21 and joined the flying school at London Aerodrome, Hendon in August 1913.[1]

Scotland passed his official flying tests on 23 October 1913 and was awarded British Aviator's Certificate No. 658 – only the second New Zealander to do so. (J.J. (Joseph Joel) Hammond was the first.) After getting his certificate, he bought a Caudron type ‘C’ biplane for £400, nicknamed Blue Bird because of its turquoise-blue finish. The aircraft was manufactured by the Société des Avions Caudron founded by brothers Gaston (Alphonse) and Rene Caudron in France in 1909. It was shipped to New Zealand on the Rotorua and arrived in Wellington on 7 January 1914. Will had arrived back in Auckland two days before, on board the Victoria.

Selling the idea of flight to the public

Once home, he joined New Zealand Aviation Ltd to give aerial exhibitions in various centres. In an attempt to popularise aviation and promote commercial opportunities, the company arranged for him to make a series of cross-country flights from Invercargill northwards, putting on flying displays at stops along the way.

In preparation for the flights in the South Island, Scotland made some practice flights near Otaki, north of Wellington. He crashed on his first attempt, but Blue Bird was quickly repaired and Will made a successful 20-minute flight there on 29 January 1914. A memorial plaque now marks the flight.

The team then travelled by ferry to Christchurch, and by rail to Invercargill, arriving on 15 February. The weather was not suitable for flying for the first few days, but on the evening of 20 February, Will flew from Invercargill to Gore.

This was the first occasion on which an aircraft had been flown in the South Island.

You can hear an eye-witness account of the flight here.

The team then travelled to Dunedin, again by train because of weather, where Scotland gave a demonstration flight at Tahuna Park on 28 February despite strong southerly winds. There was enormous interest in the flight. “Almost all of the crowd on the sandhills expressed great patience and eventually saw the biplane soaring beautifully like a dragon fly”.[2] He made another ‘charming flight’ on 1 March over Mornington and South Dunedin, and it was after this last flight that a collection was taken up “and the aviator later invested with a handsome gold medal”.[3] This is the medal that MOTAT now holds.

The team then moved on to Timaru by train, arriving on 2 March. There Scotland gave a flying display at the Athletic Grounds despite more bad weather – rain, wind and bitter cold. He flew from Timaru to Christchurch early on Friday 6 March. The Caudron “rose gracefully over the eastern fence and took the air amidst great cheering from the delighted onlookers”.[4]

"Words cannot describe the charm and beauty of the sight"

Scotland followed the railway line north, dropping a parcel as he flew over the Temuka railway station for J.G. Andrews, proprietor of the Temuka Motor Garage. It contained a handbook for the Zenith carburetter, a type used in the Blue Bird’s Anzani engine, and a letter.

After 30 minutes’ flying, Will had to stop at Orari to fix spark plugs. That accomplished, he continued to Christchurch where a crowd was waiting at Addington Showgrounds. As the Christchurch Sun reported: “The privileged few who were present on the Addington Showground yesterday, when the young New Zealand aviator, Mr J. W. H. Scotland, landed after his great cross-country flight of 100 miles from Timaru, will never forget the incident. It was the first time that an aeroplane had been seen in flight in Christchurch, and- the occasion had therefore a distinct historic interest.”[5]

It had taken him 2 hours, 5 minutes to fly the 98 miles from Christchurch from Timaru. This was a long-distance air record for New Zealand, which stood for more than five years.

The Sun’s reporter was poetic in describing Blue Bird’s arrival: “The evolutions of the machine above the grounds were most beautiful to watch. The sun was just sinking … and the western sky was flecked with little white gilded clouds. The plane passed and repassed, a rapidly moving black square against the dazzling white. As the slanting rays caught the shining green of the planes, they shone like gold. Words cannot describe the charm and beauty of the sight; no wonder the spectators were enthusiastic.”[6] The words remind us how novel this flight was.

Scotland told reporters that the flight had been very bumpy, making it very difficult to control the aircraft at times. “I was knocked about a great deal by the puffy winds. On two occasions the machine was almost turned right over, and I began to be a bit apprehensive.”[7]

While in Christchurch he did flying displays that were reported in great detail in the local newspapers. On 7 March, 4000 people watched his exhibition flight at the Addington showgrounds. “The whole flight was a very fine one, and everyone present saw a good exhibition of real flying. Scotland has established his reputation as a first-class aviator, and his future flights in Christchurch should attract even larger attendances.”[8]

The last flight of Blue Bird

After Christchurch, Scotland returned to Wellington by ferry, followed two days later by his biplane (also on the ferry) to a base at Athletic Park in Newtown. Once again, the weather was bad, with strong southerly winds, which meant he was unable to give the advertised flying displays. Despite the weather, and perhaps because of public pressure, he agreed to make a flight on 25 March. He was successful in getting off the ground, but then was undone by the wind and weather, crashing into trees in Newtown Park. Miraculously, he missed buildings and electrical wires and was unhurt, but all the wood, wire and canvas of Blue Bird was smashed to bits. People who had rushed to the scene from nearby Athletic Park fought for pieces of fabric and splinters of wood to take home as souvenirs.

Although Blue Bird’s engine was still in running order, Scotland decided not to try and rebuild the aircraft, but to order a Type ‘F’ biplane from the British Caudron Company. It was shipped to New Zealand on the Kaikoura on 4 July to arrive in late August, but international events intervened. The First World War was declared on 4 August that year, and Will immediately offered his services to the New Zealand government, which did not take up the offer.

The second Caudron arrived in Christchurch in September. Scotland had thought he would use it to make passenger flights in southern towns and cities, and run an airmail service between Christchurch and Timaru. The Type ‘F’ was bigger than Blue Bird and was hard to assemble because the makers did not send blueprints or working drawings. It was also hard to fly, and Scotland crashed it and wrecked it on a test flight. It was not able to be fixed, but the engine was displayed and run at various A&P shows in the southern South Island to enormous interest.

Off to war

Will Scotland caught diphtheria in October 1914 and spent three months in Christchurch Hospital. He then enlisted in the Royal Flying Corps and left for Mesopotamia in July 1915 to support British and Indian troops by making patrol flights. He got diphtheria again while there and returned to New Zealand in 1916, where he was offered the position of instructor with the Canterbury Aviation Company’s flying school, but he was not well enough to accept. Sir Henry Wigram established the Canterbury Aviation Company as a private flying school in 1916, and as New Zealand had no air force, the company (along with the New Zealand Flying School in Auckland) trained pilots for service in Britain during the First World War.

Scotland’s health did not improve after his return home, and he relinquished his commission with the Royal Flying Corps in November 1916.

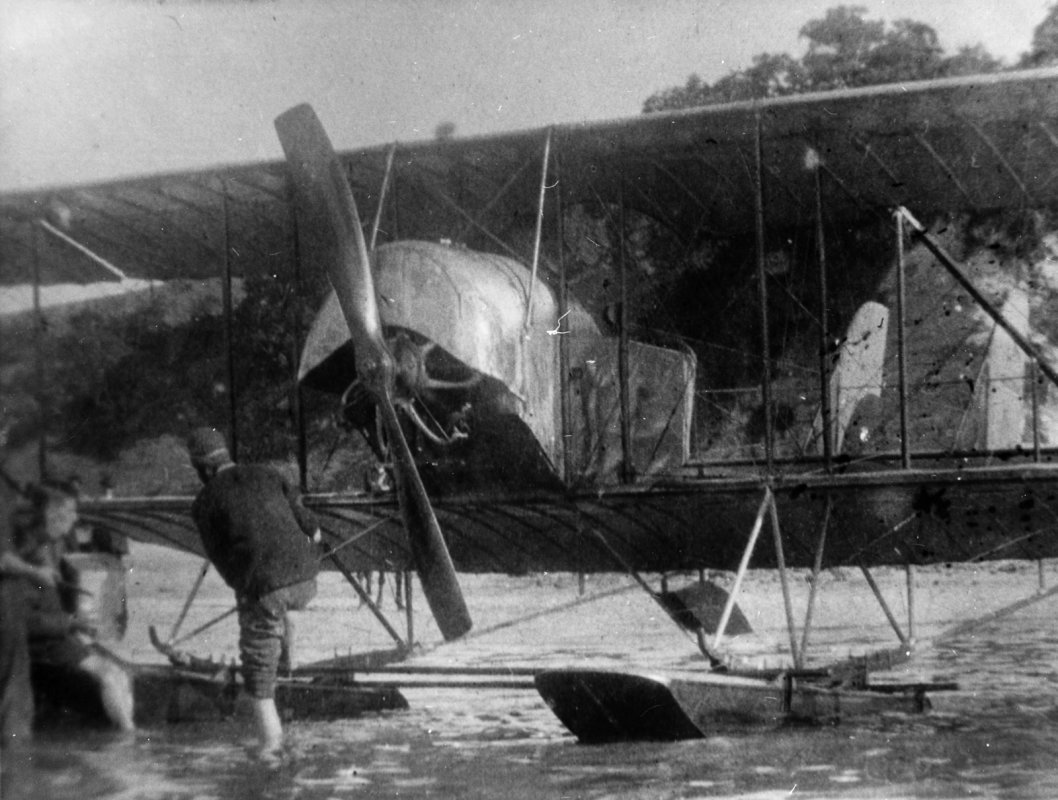

His Caudron, meanwhile, was acquired by the New Zealand Flying School at Mission Bay, Auckland and rebuilt, with modifications including floats. First flown by Vivian Walsh on 13 December 1915, it became the school’s solo practice machine and, with its modifications, was New Zealand’s first, twin-float seaplane.[9]

In memory of Scotland's famous flight

By 1919, Scotland was living in Palmerston North and working for an insurance company. He met Mabel Louisa Kennerley, and the couple were married in Sydney in 1925. They lived in Auckland, but in 1936 emigrated to Melbourne where Scotland died on 19 November 1963.

On 6 March 1964 there was a re-enactment of his famous flight from Timaru to Christchurch to mark its 50th anniversary, with John Switzer flying the route in ZK-ASP, a 1934 de Havilland Fox Moth.[10] Other memorials to Scotland’s flights include a plaque that commemorates his flight from Invercargill to Gore and the Will Scotland Memorial Air Race for de Havilland Tiger Moths, which is occasionally staged over that route. There is also a plaque near Otaki, next to State Highway 1, south of Otaki River that was unveiled on 27 January 1996, and marks where Scotland made his first test flights in Blue Bird.

Contemporary description of Scotland’s Caudron ‘C’ biplane, Blue Bird

“The machine is a Caudron biplane, invented by the Caudron Freres in France. This machine is different from every biplane in that it has flexible wings, making it a perfectly distinct type. It has a large tail, also flexible. The effect of this flexibility gives great stability to the machine, and makes it one of the safest and lightest machines now flown. As a matter of fact, it is the lightest machine made, and is the only biplane which [NP1] will fly successfully with a low horse-power. This, coupled with its stability and easy control, makes it an ideal machine for school work. The plane is strung on the chassis with elastic bands, which absorb the shock when landing. The chassis is extended right to the tail by means of extension struts, which run along the ground when the machine has landed, acting as an-efficient brake. By this means the machine can be pulled up in a very short distance, as was evidenced by Mr Scotland's magnificent descent yesterday afternoon. The steering gear is manipulated by foot control, which works twin rudders above the tail plane. The aviator's seat is situated in a nacelle placed between the two main planes, almost in front of the machine. In front of the nacelle the engine is bolted on to its plate It is a 45 h.p. Anzani, with six cylinders. It gives 1800 revolutions. The tractor is fixed on to the front of the engine. It is made in six pieces and is a product of Helice Mercure, Paris. The material is French walnut. The top main plane spans 34ft [10.36m], and is 5ft [152cm] in depth. The bottom plane is 22ft [6.70m] long. The control is manipulated by a central lever. By moving it backwards and forwards the aviator gets elevation or depression, and by moving it sideways he gets the necessary warping of the planes [NP2] [BN3] for counteracting side winds and air currents. The tail warps in conjunction with the wings. The total weight of the machine with the engine is between 500lb [c227kg] and 600lb [c272kg]. With the oil and petrol tanks now fitted a flight of four hours can be undertaken. The machine is very speedy, as was proved in the Invercargill to Gore flight, when an average velocity of 80 miles [c129km] an hour was attained. The Caudron machines have gained great prominence at all aviation meetings, on account of their speed, safety, and reliability. The monoplane made by the same firm is the fastest in the world. It holds the record for French military competitions.” Christchurch Sun newspaper, 7 March 1914, p. 10

Significance

Will Scotland was the last of the New Zealand aviation pioneers who flew before the First World War began in 1914. While his flying exploits have been largely overlooked in New Zealand popular aviation memory, where Richard Pearse and – in Auckland – Leo and Vivian Walsh and their New Zealand Flying School tend to be the names that spring to mind, the medal and collection of photographs and ephemera at MOTAT recognise the significance of Scotland’s achievements.

These were the early days of aviation – Wilbur and Orville Wright had first flown in December 1903 and Vivian and Leo Walsh in Auckland in February 1911 – and few New Zealanders had seen an aircraft. Commercial flying ventures, such as Scotland was involved with, were very popular at the time. The size of the crowd that came to see Scotland fly, and that people were prepared to pay one shilling each to do so, is evidence of the novelty of such displays.

When Will Scotland flew from Invercargill to Gore on 20 February 1914, it was the first time that two New Zealand towns had been deliberately connected by air. Some have claimed that, by dropping a parcel over Temuka, he delivered the first letter by air in New Zealand, but the feat was not official as it had not received the New Zealand Post Office imprimatur. While it may have been the first time that such a thing happened, it cannot be recorded as the first official airmail delivery in New Zealand.

Scotland’s cross-country flights, however, did illustrate the possibility of regular airline services, including mail, in this country. His flights have been described as the first to take aircraft “beyond the mere public spectacle and properly explore the skies.”[11]

Scotland also had the connection with Sir Henry Wigram’s Canterbury Aviation Company, which flew from Sockburn airfield near Christchurch. In 1923 the New Zealand government purchased the land and assets of the company for its newly-formed Permanent Air Force. Renamed ”Wigram”, the airfield was the Royal New Zealand Air Force’s main training base until 1995.

Neither of Will Scotland’s Caudron biplanes survives, although the propeller of Blue Bird is held by the Museum of Aviation in Kapiti. [12] Together, MOTAT’s J.W.H. Scotland Collection and the propeller at Kapiti, along with the two plaques and the irregular memorial air race remind us of these early days of flight in, to modern eyes, such flimsy and improbable aircraft.

Story by Megan Hutching

References

E.F. Harvie, Venture the Far Horizon: Epic flights by New Zealand’s pioneer aviators, Christchurch, Whitcombe and Tombs, 1966

John King, Famous New Zealand Aviators, Wellington, Grantham House, 1998

[1] Biographical information about Will Scotland is based on a chapter in E.F. Harvie, Venture the Far Horizon: Epic flights by New Zealand’s pioneer aviators, Christchurch, Whitcombe and Tombs, 1966

[2] Harvie, p. 40, quoting Evening Star newspaper

[3] Harvie, p. 42

[4] Harvie, p. 43 quoting the Timaru Post

[5] Sun, 7 March 1914, p. 7

[6] Sun, 7 March 1914, p. 7

[7] Sun, 7 March 1914, p. 7

[8] Sun, 7 March 1914, p. 10

[9] Harvie, p. 73

[10] John King, Famous New Zealand Aviators, Wellington, Grantham House, 1998, p. 33

[11] King, p. 33

[12] https://www.nzmuseums.co.nz/collections/3190/objects/27346/scotlands-propeller

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/SUNCH19140307.2.79?end_date=07-03-1914&items_per_page=10&query=scotland&snippet=true&start_date=07-03-1914&title=SUNCH

Find more stories about the past, present, and future technology of Aotearoa here.