Open Wide: A Short History of the Murder House in New Zealand

Dentist Sign, T152. The Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT).

Many businesses such as dentists and hairdressers have been overwhelmed with bookings after the return to ‘normal’ life post Covid-19 lockdown here in New Zealand. It makes you wonder: a rush to the dentist is usually unheard of because, for many, the idea of the dentist conjures up images of pain and cold, clinical sights and smells.

But where did this anxiety come from? This article aims to delve into the history of the School Dental Service (SDS), the school dental clinics also known by my parent’s generation as the ‘murder house’, and bring our worst fears into the light. Did it succeed in improving children’s oral health? Was the ‘murder house’ really a place of trauma and pain?

Early Dentistry

Dentistry has been practised throughout New Zealand since the mid-19th century. Early dentistry was primitive, with no local anaesthetic, and only hand-held drills. In the 1870s, however, new technology began to advance dentistry practice. This included adjustable dentist chairs, a foot-pedal-operated drill, and a range of materials used for fillings, false teeth and pain control. The Dentists Act of 1880 required dentists to register and fulfil a set of requirements, and a Dental Board was initiated to examine those applying for registration. The latter was eventually disbanded, although the 1904 Dentists Act stated that dentists were required to have at least two years of study. In 1905 the New Zealand Dentists Association (NZDA) was formed to represent registered dentists, and by 1908 the first Dentistry School had opened in Dunedin with 20–25 students.

School Dental Service (SDS)

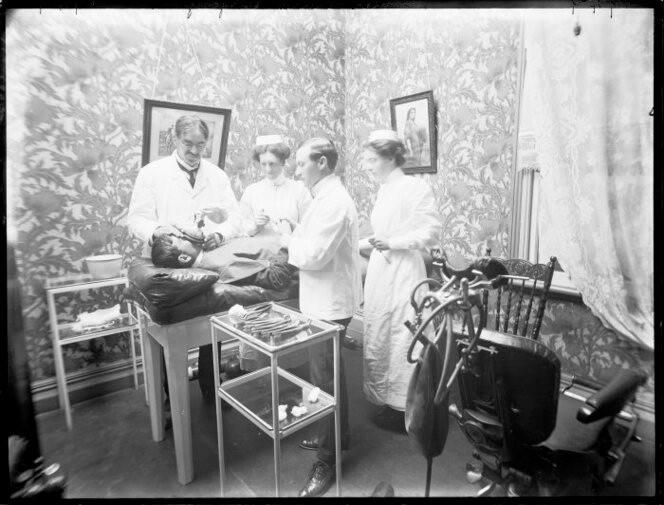

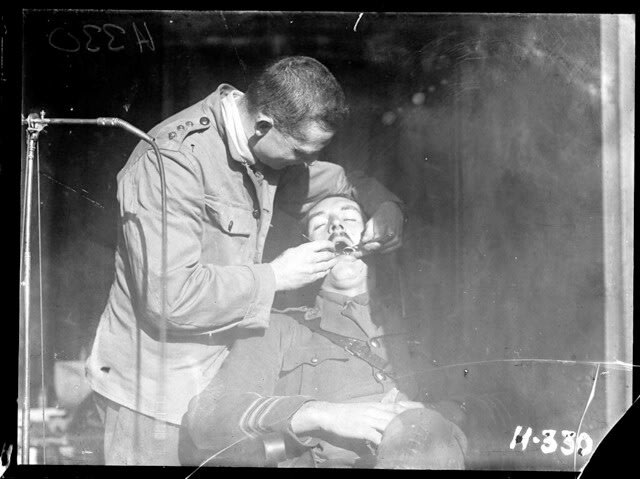

World War One was a major catalyst for further advancements in dentistry. Recruits were found to need extensive dental treatment in order to be fit to serve. This highlighted the need to move away from a focus on tooth extraction towards prevention of disease. Colonel Thomas Hunter, the director of the Department of Health advocated for a School Dental Service to treat primary school children and this was established in 1921 — a world first! The SDS recruited ‘suitable young women’ to participate in a two-year course which would provide them with the training needed to treat primary school children. Young women were regarded as being better suited to treating children, cost less to employ (no equal pay in those days!) and less time to train compared to their dentist counterparts. Consequently, the first Dental Nurses School was opened in 1921 in Wellington with 35 female students.

Dental nurses, 1941. Ref: 1/1–019015-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

SDS: Successes and Challenges

The Great Depression and World War Two affected the SDS during the 1940s. Due to a higher number of children born post-war, compared to a lower number of dental nurses born during the Depression, the SDS struggled to keep up with demand. The various polio outbreaks during the 1940s and 1950s and associated school closures resulted in a further strain on services due to lack of staff and its effect on the patient recall system. Nevertheless, oral hygiene continued to be a concern amongst health officials, as part of the attempts to improve children’s health. One such activity was the toothbrush drill, seen in the photograph below.

Children at a toothbrush drill, Okato School, Taranaki. Taylor, R M S: Photographs relating to dental nursing. Ref: PAColl-7112–04. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

In 1937 the government introduced free milk for primary school children, in an initiative to improve teeth and bone health through the calcium that milk provides. Milk monitors provided each child with half a pint of milk (300ml) per day, although milk would often become warm as schools did not have chillers, so it was not loved by all. The free milk programme ended in 1967.

Auckland school children drinking the daily issue of free milk. Ref: MNZ-2461–1/4-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

Another positive outcome of the SDS was a new awareness of the dental care of Māori children. In the 19th century Māori often had better teeth compared to Pākehā, due to eating less often and having a lower sugar intake. By the 1920s and 1930s both Māori and Pākehā were considered to have equally bad teeth. As a result, the SDS trained four Māori dental students to care for Māori children, particularly in rural areas, where Māori children often attended Ngā Kura Māori/Native Schools. By 1929 all schools were able to establish their own dental clinics, yet by the mid-1930s few Native Schools had access to dental clinics. From the 1940s onwards, the New Zealand Government has pushed for more dental accessibility for Māori, and whilst the margin has narrowed, in the early 2000s there were still inequalities between the oral health of Pākehā compared to Māori and Pasifika children.

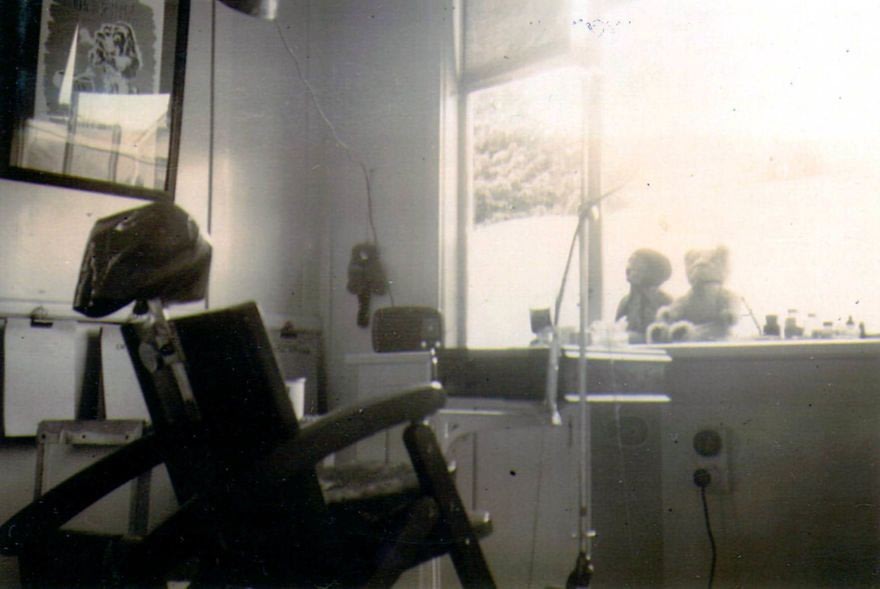

Interior of the Shannon School Dental Clinic (The Murder House) 1949. Horowhenua Historical Society Inc.

Whilst the SDS may have been regarded as a highly successful operation by officials, the School Dental Clinics earned themselves a different sort of reputation with the children of New Zealand. First recorded in 1964, school dental clinics were nicknamed the ‘murder house’. Regarded by many children as a place of pain, the school dental clinic was often a lone wooden building within the school grounds, often separated from the main buildings. The clinic became the centre of many spooky stories. Aided by the remote location, the sharp metal objects held within, the accompanying medical smell, and the strange woman in the white and red uniform who you only saw when you visited the clinic, the ‘murder house’ wove itself into the cultural fabric of New Zealand society.

Screenshot from the 1998 NZ Short Film “The Murder House”.

The 1998 New Zealand short film, ‘The Murder House’, directed by Waka Attewell and written by Ken Hammon, is a satirical take on this social myth. The film centres around one boy’s visit to the school dental clinic. Classed as a horror, this film summarises the fear that gripped children of the period.

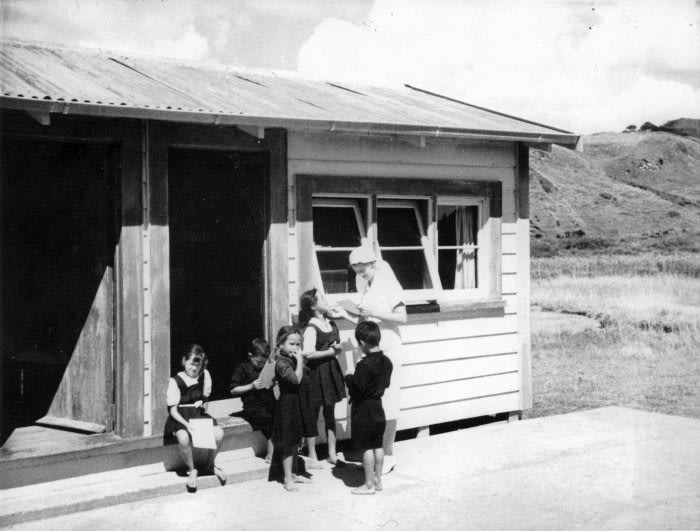

Exterior of Dental Clinic, Shannon School, c.1950. Horowhenua Historical Society Inc.

Susan Cartwright’s thesis from 2010, is titled, ‘The Murder House Case Studies: An Education in Dental Anxiety”. For her these, Cartwright interviewed people who experienced the anxiety of visiting the ‘murder house’. One stated,

‘I can see the little building which was a separate building from all the other classrooms on this little patch of grass’.

Another commented,

‘why did they stick it there — perhaps so that you couldn’t hear the screaming? It was not at all child friendly. It had that awful detergent-like smell, and noises like the clanging of instruments in the old tin boxes where they would put their nasty equipment and boil it up’.

Many participants described dental nurses as:

‘impatient, uncaring, showing no understanding of anxieties, cold, European, older, large (perhaps because participants were small children), a butcher, a sadist, brutal, rough, with no gentleness, like a strict matron, stressed, frustrated, and scary’.

One participant stated,

‘we used to call it the slaughterhouse for a good reason��… she was a butcher. She would rip your teeth out without giving you an injection and if she did… I have quite deep roots, and if she did give you an injection she was so rough and shoved that needle in so fast it was just excruciating. So I think she was a bit of a sadist…’.

Despite this, a participant stated that it was not the fault of the dental nurse:

‘I can see her in her starched white outfit. She was friendly in the playground. She wasn’t a witch…generally she was a woman who was quite motherly…she wasn’t a figure of fear. It was more to do with the place. It wasn’t her. It was the environment. We didn’t associate her. It was like; it was almost like we understood this was her job and that she had to do it. It wasn’t her fault somehow. She wasn’t a murderer. It was a murder house…’.

Ultimately, though, many children held the view that the school dental clinic was a place of pain.

The Murder Weapons

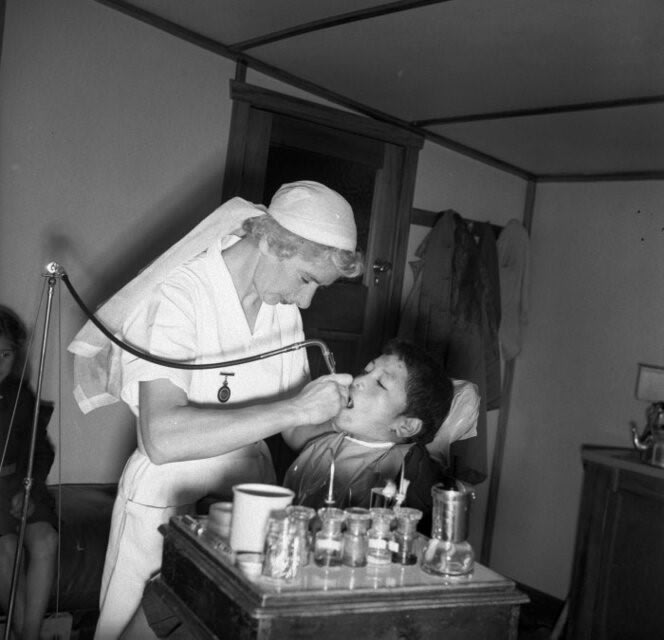

School dental nurse and patient. Ref: 1/4–000037-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

Many school children of the mid to late 20th century will be familiar with the scene in the photograph above. Taken at Waipu School, circa 1942, it shows a student seated in an adjustable chair, being treated by the dental nurse. A pedal-operated treadle drill can be seen in the background.

Dental Chair, 2016.48. Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT).

MOTAT holds an example of the same type of dental chair. Built in New Zealand, likely between the 1940s and 1960s, the frame is made from kauri and has a detachable footrest. The height of the chair can be shortened or lengthened using a metal chain which is connected to the two legs and is secured by a metal pin. The back of the chair can also be adjusted with a metal pin slotting into the desired slot or a series of cut-outs along the interior of each armrest. The footrest can be attached to the lower rungs on the chair, and the padded vinyl headrest can be moved up and down with two wooden knobs. Primary school children would sit on this type of chair to receive their dental care from a dental nurse.

Dental Drill, T5905. Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT).

MOTAT also holds a foot-operated dental drill. Invented in 1871, treadle drills were used well into the 20th century. Electric drills only became available in the 1920s and were finally used in dental nurse training in the 1950s. Until then, primary school students faced the treadle drill. Made from cast iron, the drill is placed on a three-pointed base and vertical support. A large wheel is attached to this and on the opposite side of the axle is a vertical lever leading down to the foot pedal. The dental nurse would operate the machine with the foot pedal (shown on the right in the photograph), allowing both hands to be free to work on the patient’s mouth with the drill.

Electric Portable Dentist Drill, 2015.93.1. The Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT).

After the treadle drill, portable, electric dentist’s drills were developed. This photograph depicts the electric drill held in MOTAT’s collection. Made by Kaltenbach & Voigt in Germany circa 1950, this drill was used by the Auckland School Dental Service from the 1960s and donated to MOTAT in the 1980s. The drill is driven by an external motor, the speed of which is controlled by a foot pedal. The drill handpiece was fitted with replaceable metal tipped dental burs of different shapes.

Dental Wash Basin, T5916. The Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT).

MOTAT also holds an example of a traditional dental basin. Cream in colour, the ceramic basin is attached to a metal stand. Connected to the stand is a metal bracket which holds a tray for the dentist to place their tools. Another metal bracket holds the piping, protruding up from the other side of the basin. This includes a long, thin metal tap for water to dispense and two smaller taps. A rubber pipe emerges from the base, and the stand has three holes in which it can be attached to the floor. Modern dental basins are similar in design.

Range of Dental Accessories. The Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT).

This photograph shows a range of tools that would have been used by dental nurses in the ‘murder house’. The sharp metal instruments are still used today, and include a small mirror, filing tools, tweezers, excavators, scalers and a spatula.

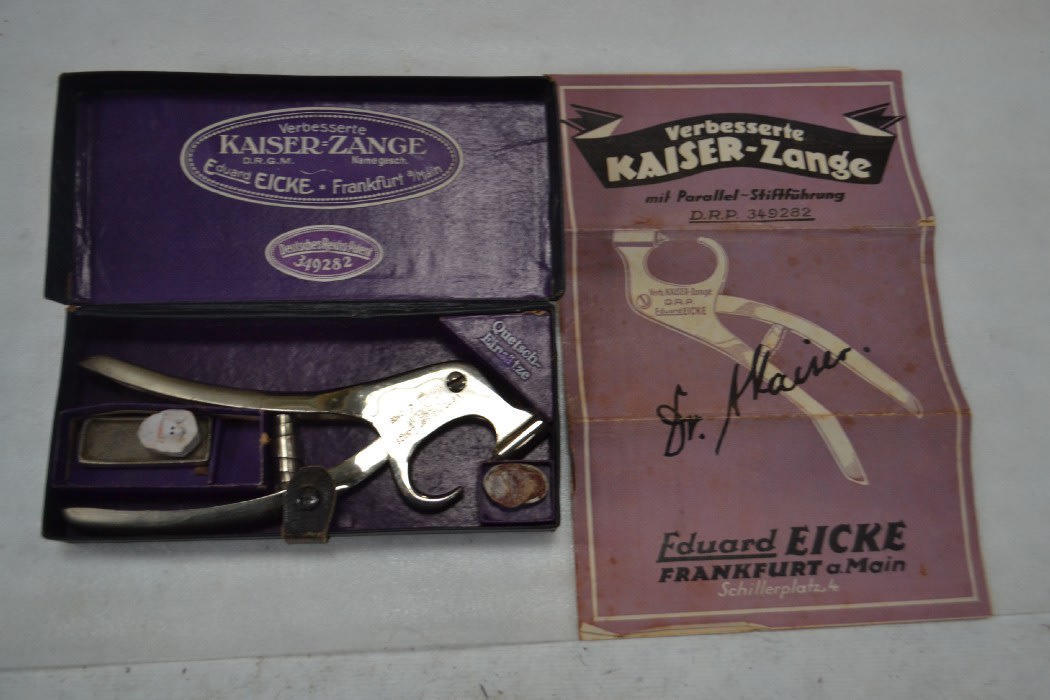

Equipment — Dental, F1889.2004. The Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT).

A dental mouth separator, this object was used to keep the patient’s mouth open and was possibly needed for children terrified of visiting the ‘murder house’. The separator consists of two curved pieces of metal with hooked ends, which opened and closed with a hinge and featured a lock mechanism which could hold the item to a specific width inside the patient’s mouth. Rubber was attached to the hooked ends for the patient’s comfort.

Dental Forceps, T8420. The Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT).

Featured above is an example of dental forceps, held inside the original packaging along with the instruction manual. Made from stainless steel, this object has a curved handle and spring in the centre. At the end is a large bracket, wide enough to fit around a tooth, and a pincer mechanism is attached. Local anaesthetic was not used in early dentistry and not often in dental clinics. A participant interviewed for Cartwright’s thesis said of their experience with teeth pulling:

‘I had a tooth removed and I’ll never forget…she didn’t give me anything. She just pulled it out and she was as rough as… just shove the thing… and I remember there was bruising around my mouth and another time she injected and she would just give one injection and it was always rough and you would always have loads of the stuff in your mouth. She didn’t take care. You know normally they take it out and you don’t get all that liquid. It’s quite bitter and horrible’.

School Dental Service — The 1980s and Beyond

Dental Nurse, Cape Runaway clinic, early 1940s. Ref: PAColl-7112–02. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

By the 1980s Dental Nurse numbers had dropped due to a wider social acceptance of women in a wider range of professions, as well as women returning to work after having children. Dental nurses were called dental therapists by the 1990s and by 2004 were no longer limited to working for the SDS but could also work in private practices. A new vision regarding oral health for all New Zealander’s was introduced in 2006, with major changes to the SDS including more funding for new clinics, building up the dentistry workforce, and a focus on dental disease prevention. As a result, children’s oral health seems to be improving.

Despite the infamous nickname for dental clinics, the SDS successfully raised awareness of the importance of looking after teeth. By teaching children good oral hygiene practice, it will help reduce the risks of oral disease in the future. MOTAT’s dental objects highlight the developing technology in dental care over the twentieth century, and the social history that accompanies these objects. While the ‘murder house’ has woven itself into the cultural fabric of New Zealand society, is the dentist still regarded as a place of pain and torture? A participant in the dental anxiety study stated,

‘my current experience of dentists is only positive. The fear remains from classical conditioning, and I am convinced [it]will fade with generations removed from the House of Pain.’

And that’s the tooth!

REFERENCES

Cartwright, Susan. 2010. The Murder House Case Studies: An Education in Dental Anxiety. School of Education. Accessed: 23 June 2020, URL:https://openrepository.aut.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10292/1043/CartwrightSH.pdf?sequence=3

Moffat, Susan and Andrew Schmidt. Dental Care. Te Ara — the Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Accessed: 23 June 2020, URL:https://teara.govt.nz/en/dental-care

Moffat, Susan, Lyndie A. Foster Page and W. Murray Thomson. New Zealand’s School Dental Service over the Decades: Its Response to Social, Political, and Economic Influences, and the Effect on Oral Health Inequalities. Front Public Health. 2017; 5: 177. Accessed: 23 June, 2020, URL:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5534465/

New Zealand Dental & Oral Health Therapists. Our Story. Accessed: 23 June 2020, URL:https://nzdohta.org.nz/about/about-us/our-history/

New Zealand History. End of Free School Milk. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Accessed: 23 June 2020, URL:https://nzhistory.govt.nz/end-of-free-school-milk#:~:text=The%20scheme%20lasted%20until%201967,their%20daily%20ration%20of%20milk.

NZONSCREEN, 1998. The Murder House. Accessed: 23 June 2020, URL: https://www.nzonscreen.com/title/the-murder-house-1998/overview

CITE THIS ARTICLE:

Hames, Emily. Open Wide: A Short History of the Murder House in New Zealand. MOTAT Museum of Transport and Technology. First published: 10 July 2020. URL www.motat.nz/collections-and-stories/stories/open-wide-a-short-history-of-the-murder-house-in-new-zealand