Martin Jetpack lands at MOTAT

Chasing a hydrogen-fuelled dream

From flying rucksacks, to flight packs, to rocket belts, the Jetpack has held many different names. What connects each of these inventions is being a wearable device that lifts the pilot through propulsion. The idea was first patented in 1919 by Russian inventor, Alexander Fedorovich Andreev. However, this first iteration never made it past the drawing board. While many continued to try, the first successful recorded attempt was achieved by Wendell F. Moore of Bell Aerosystems in 1960. His Bell rocket belt required five gallons of hydrogen peroxide to sustain a 21-second flight. When demonstrated to the United States military the limited distance was not considered impressive enough and they did not proceed with funding Moore's work any further.

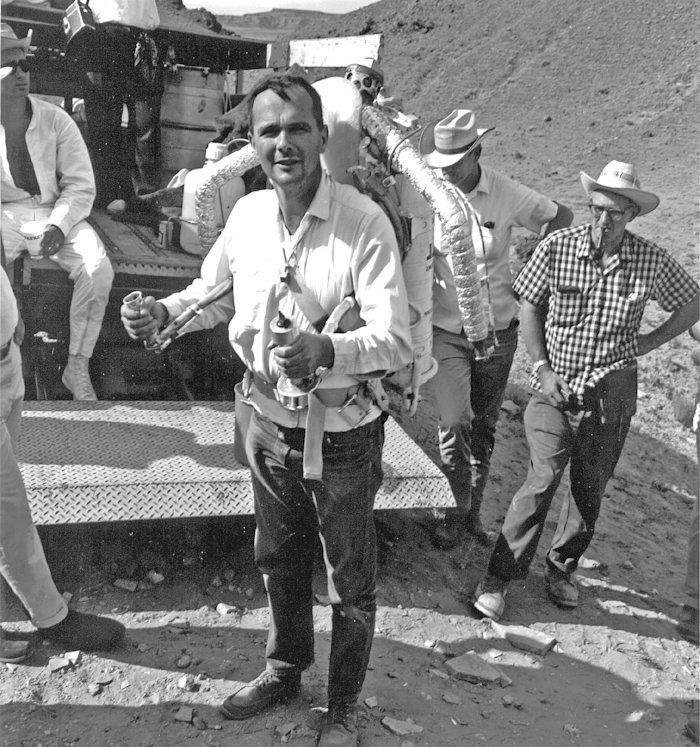

Gene Shoemaker donning a Bell rocket belt. 1966.

Despite this early failure, jetpacks continue to fuel the imagination of engineers and many different attempts were made to extend their flight time beyond a single minute. New Zealand inventor Glenn Martin was the first person to achieve this with a jetpack that could travel 50km in 30 minutes. His Prototype Number 10 (PRO-10) Jetpack was built in November 2006 in Christchurch by the Martin Aircraft Company (MAC), that he founded in 1998. It was one of several jetpacks developed by the company in the pursuit of creating a marketable jetpack.

Martin wanted to develop a product more competitive and practical than his predecessors. The American Flying Belt had been the last company to try designing a jetpack in 1994 but had only been able to extend the flight time to 30 seconds before the company went under.

Martin described his dream of building a jetpack as being embedded in his childhood watching the space race of the 1960s.

“I suppose we all thought that we were going to be flying around in jetpacks and having bases on Mars and having flying cars when I grew up and, in the end, that never happened.” (1)

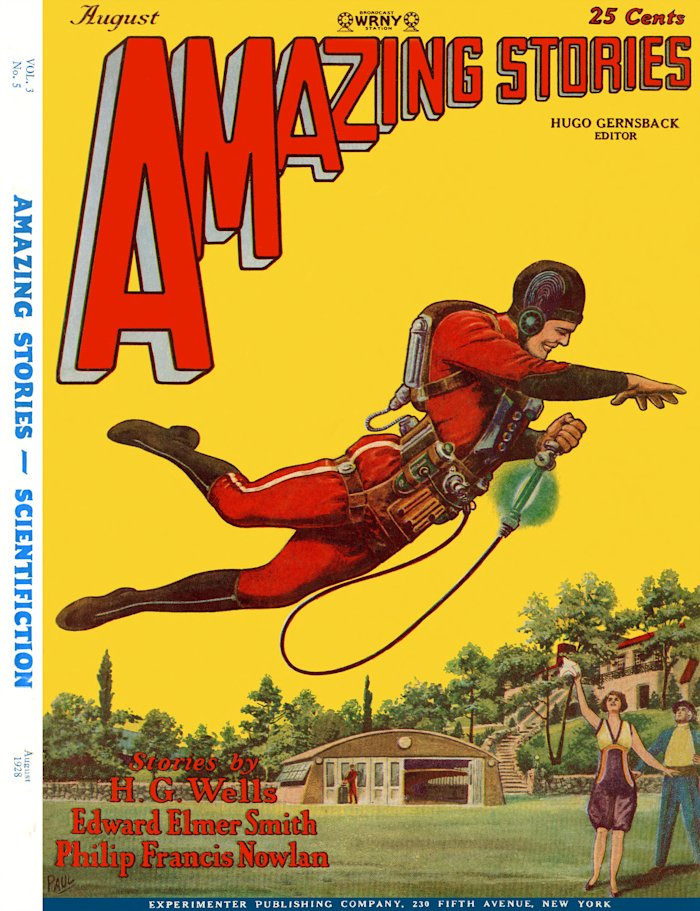

Illustrator Frank.R.Paul. Amazing Stories. August 1928 (Volume 5, no.3)

This imagining of the future was shared by the general public and was reinforced by 1960s television shows such as The Jetsons, Star Trek and Dr. Who. Jetpacks worked their way into the public image of the future partly through the efforts of Wendal F. Moore who, after his failed military demonstration, had hired a Hollywood agent. His jetpack was worn by Sean Connery as James Bond in Thunderball, and featured in the 1984 and 1996 Olympic opening ceremonies, as well as in various Disney theme park presentations and TV shows. While Moore’s jetpack remained limited by short flight times, Glenn Martin was working on a jetpack that would go beyond an entertainment gimmick.

“By about 1981 I was at university … I went off to the science library and starting researching [a jetpack] … I just did it really as an intellectual exercise. I’ve always said to myself I would stop when I could prove it couldn’t work but, in fact, the opposite has happened.” (2)

Martin spent the years leading up to establishing the Martin Aircraft Company (MAC) investing his spare time and money into the project. In 1998, he made the leap to establish a business and dedicate himself full time to making his ideas a reality. It is a dream that had staying power, with research and development lasting over 35 years. Encouraging this dream was Chief Test Pilot for MAC, Prospero ‘Paco’ Uybarreta who, in 2016, said that while their competitors' unmanned and autonomous flying devices had been on the rise, there was still a desire for humans to experience flight. Products like jetpacks and other personal air vehicle concepts helped to realise this.

While the Martin Jetpack never realised commercial success it significantly pushed forward the parameters of human flight and lifted jetpack technology beyond single 30-second jumps.

The Martin Jetpack

The idea behind the Martin Jetpack was for a Vertical Take-off and Landing (VTOL) device that people could fly without the cost or training required to obtain a pilot’s licence. To avoid the pilot's licence requirement Martin had to ensure the jetpack met all legal requirements set out in the Ultralight Regulations of the US Federal Aviation Administration. To achieve this, it was necessary to control the jetpack’s weight, fuel capacity and speed. This is part of what made the Martin jetpack such an innovative invention, because the balance that had escaped inventors of the past was finally realised as lift, range and weight were perfected to create a light but powerful jetpack.

Detail of the belt-driven ducted fans on PRO-10. MOTAT, 2021.56

How the Jetpack was controlled in flight

Martin’s PRO-10 Jetpack achieved lift using belt-driven ducted fans that were powered by a petrol engine connected to a driveshaft. This formed the basis of the propulsion unit for the different models of jetpacks that were developed between 1998 and 2019. The propulsion unit off an airplane has essentially been removed and strapped to the wearer's back.

The PRO-10 has two ducted fans that flank either side of the pilot. Below the fans are vanes or aerofoils that are steered by the pilot to control flight. When the pilot moved the position of these vanes, the direction of flight changed by redirecting air generated by the powered fans. This is termed "yaw", one of the three types of motion that are controlled in powered flight. Pitch (elevator) and roll (side-to-side), the other two types of aircraft motion, were controlled by the pilot's body. To roll left, the pilot would lean to the left – the same as is done when riding a motorcycle. On fixed-wing aircrafts, pitch and yaw are controlled by ailerons and elevators, while yaw is controlled by the tail rudder, along with ailerons.

Propulsion and power

The fans of the PRO-10 were first powered by a Rotax 3-cylinder engine. Rotax engines are known for their use in ultralight and light aircraft, along with unmanned aerial vehicles. However, this 3-cyclinder engine was found to be not powerful enough for the jetpack. The fans needed to go faster, and more torque was required to generate sufficient power. Greater power generation was limited by the revolutions per minute that the Rotax engine could deliver. When testing the jetpack, the Rotax was found to weaken around 5000rpm, limiting airflow generated through fans required for greater lift. A more bespoke solution was developed.

The prototypes that followed the PRO-10 helped engineers develop a V4, single-cylinder motorcycle engine. Different combinations were trialled using CAD designs, factoring in weight disposition according to different cylinder arrangements. They tried layouts including four cylinders opposed; a tight V; a less inclined V; and a straight inline assembly. The final arrangement was a V grouping of the cylinders. Weight was also impacted by different designs for the engine’s crank case. One engineer said it came down to weight in grams to get a final solution that bought the PRO-10 to under 114kgs (the upper limit for microlight aircraft).

The custom V4 was eventually replaced for an off-the-shelf model produced by British-made company Gilo Industries, a Rotron, which was an aircraft equivalent of a Maxda RX6 or RX7 engine.

Video: The journey to the PRO-10 – testing for flight capability

The PRO-10 was not the start of the journey for the Martin Aircraft Company – nine earlier jetpack prototypes had been created, each one furthering the team towards their final goal. One early test of Martin jetpacks included attaching a prototype of the propulsion unit to a hang glider. Glenn Martin was an experienced hang glider and applied that experience to the jetpack trials. As the propulsion unit was developed, the unit was attached to a pole in the Martin’s garage to test lifting capabilities.

The PRO-9 was the next iteration of the jetpack and this prototype was tested on a wire suspended between two trees in a paddock on Tram Road in Christchurch. The PRO-9 was tethered to the wire to test forward, backwards, left and right movements, all conducted within the safety of the tethered wire. The next phase of development moved into the workshops, which had been set up in 2007.

Martin Aircraft Company Jetpack P11.1 test flight

MAC. Martin Aircraft Company Jetpack P11.1 in flight with test flight mannequin. MOTAT. PHO-2021-13.1

The PRO-10 was the fourth iteration of prototyping by the Martin Aircraft Company. Development was centered around creating a jetpack that was able to achieve lift within the microlight weight category (also termed ultralight) and produce enough power to fly distances that would lend itself to application across a range of industries. Search and rescue, along with recreational flying, were two mooted possible markets for the Martin Jetpack. Weight was a highly significant factor in development because they were working to a weight limit of 114kgs (254 pounds) – the United States specification for extremely lightweight aircraft intended for operation by a single person. 1

The PRO-10 was first tested in March 2007 in the MAC workshop, again using a tethered wire. Testing involved a trial of the revolution range for the engine and for pilots to get comfortable with the machine. Engineer Ray Thomsen termed this "wingman" testing, as there would be a person either side of the piloted jetpack to protect the pilot. The PRO-10 was also used during gimbal trolley testing, so that the jetpack could rotate around multiple axes. The jetpack was clamped onto the trolley, but the engineers soon learned they were suddenly teaching themselves how to fly a trolley and not a jetpack, so they reverted to their previous wingman method. This further testing helped realise the weakness of the Rotrax engine and pushed them into the next stage of development with the V4 engine in the PRO-12.

Reaching Recognition

Over the years, MAC received investments from several sources, and the company would go on to have international shareholders. A major success was in 2010, when the Martin Jetpack was listed in Time magazine’s Top 50 inventions of 2010 as a "most anticipated invention".

Video: 2015 Martin Jetpack Flight Demonstration, Shenzhen, China

In September 2008 the PRO-12 Martin Jetpack flew in its the first public flight at Airventure, an airshow in Wisconsin. It would go on to be shown at airshows all around the world, demonstrating the strength and speed of their invention. This marked another significant step forward for MAC as the company moved towards full commercialisation.

Despite the investment, global acknowledgements and successful test flights, change was coming for the company with Glenn Martin leaving around 2014. The company continued to pursue testing the jetpack at altitude and in adverse weather conditions, building towards a product that could be used for search and rescue operators. However, in 2021 MAC went into liquidation, with its workshops shut, and company assets sold. Their final product had a maximum speed of 74km/h and a range of 33.7 km with flight times of up to 30 minutes. Considering the 30-second flight times that their predecessors had achieved Martin Jetpacks had dramatically lifted the benchmark of what a jetpack could achieve.

MOTAT worked to acquire PRO-10 for the collection to showcase the significant work put in by the engineers of Martin Aircraft Company, which now sits as part of the history of innovators in Aotearoa. The PRO-10 features in the Forces of Flight exhibition at MOTAT’s Aviation Hall. This new exhibition explores the forces of flight and how aircraft design incorporates the forces of Lift, Thrust, Weight, and Drag. Four factors that the Martin Jetpacks engineers calculated to a meticulous degree to deliver a record-breaking aircraft.

Video: Martin Jetpack Series 1 – From Concept to Reality

Sources:

1 & 2: Martin Aircraft Company. (2015). Martin Aircraft Company Ltd ASX Listing Story. Accessed 1 July, 2024:

Asia Nikkei. (2016). Martin Jetpack lifts of 35 years after conception. Accessed 1 July, 2024: https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Martin-jetpack-lifts-off-35-years-after-conception

Jeff MacGregor. (2015). The Ill-fated history of the Jet Pack. Accessed 20 Novemeber 2025: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/ill-fated-history-jetpack-180955294/

Science Learning Hub Pokapū. (2011). Martin Jetpack – one of top 50 inventions in 2010. Accessed 20 November 2025:https://www.sciencelearn.org.nz/resources/2132-martin-jetpack-one-of-top-50-inventions-in-2010

CBS News. (2014). Jet packs in flight and fiction. Accessed 20 Novmeber 2025: https://www.cbsnews.com/pictures/jet-packs-in-flight-and-fiction/

Barry E. Digregorio. (1996). The Rocket Belt. Accessed 20 November 2025: https://www.inventionandtech.com/content/rocket-belt-1

Comment made by Chief Test Pilot, Paco Uybarreta. Martin Aircraft Company. (2016). MartinJetpack.com, accessed in 2022

MOTAT Phone call with Ray Thomsen. (2021.)

Article by Chelsea Renshaw and Susan Tolich, MOTAT Curator – Transport, with editing by Head of Curatorial Research, Belinda Nevin.

Published December 2025.