G-AUNZ Aotearoa: The Remaining Pieces of an Aircraft

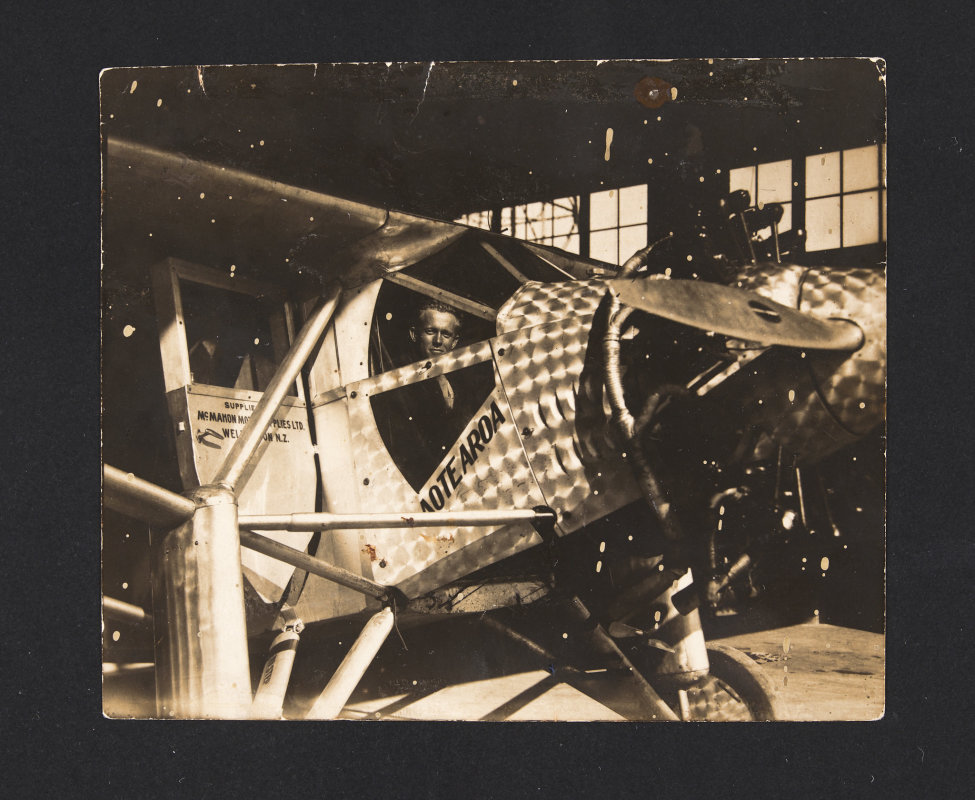

In the early morning of 10 January 1928 New Zealanders Captain George Hood and Lieutenant John Moncrieff took off from Sydney, Australia, in a single-engine Ryan monoplane, registered G-AUNZ and named Aotearoa. This was an attempt to complete the first flight across the Tasman Sea.

The 2335km flight to Trentham, just north of Wellington, was expected to take 14 hours but Hood and Moncrieff never arrived at Trentham racecourse in Upper Hutt. No trace has ever been found of the aircraft or the two men.

The Aotearoa took off from Richmond, Sydney at 2.44 am local time (5:14 am New Zealand time). The Northern Advocate newspaper reported the departure: "The chocks were pulled from the wheels, the propeller revolved and at 2.44 am, with the engine revolving at cruising speed, the pilot waved his hand as a signal of departure. The “all clear’’ was given, the monoplane taxied into the open space of the aerodrome, and within 100 yards had risen and turned direct for New Zealand. Within a few minutes, it was lost to sight and sound."

Aotearoa carried no flight instruments and the radio had no navigational capability or function, although it had been tested before take-off and was in working order. To keep track of the flight, Hood and Moncrieff had arranged to send out a continuous tone for five minutes every quarter of an hour. The signals were heard clearly at intervals at the Wellington wireless station. Shortly after 3 pm, the signals were picked up strongly, but then there was a long interval until they were heard again at 5.15 pm. Soon after this, when the aircraft had been in the air for just over 12 hours and should have been within about 200 miles of New Zealand, signals from the Aotearoa ceased abruptly. It was an anxious time but the unreliability of airborne radio at the time did not necessarily mean that loss of signal equalled the loss of the aircraft.

The two wives, Laura Hood and Dorothy Moncrieff, waited at Trentham Racecourse with thousands of others, but the Aotearoa failed to arrive. Starting on 11 January, air, sea, and land searches were carried out for many days in the hope of finding the aviators alive at sea, or on a remote beach, or at least finding some wreckage that might indicate their fate. Nothing was found.

Hood and Moncrieff’s aircraft, Aotearoa was a Ryan Brougham B-I, a small single-engine, high-wing aeroplane produced in the United States in the late 1920s and early 1930s with a fully enclosed cabin for the pilot and four passengers. It was similar to the one used by Charles Lindbergh for his successful solo trans-Atlantic flight in May 1927. Around 150 B-I types were built.

The dream of accomplishing the trans-Tasman crossing was inspired by flights such as Lindbergh’s, along with a desire for adventure and exploration propelled the dream forward. Alongside these emotions ran a more practical proposal – that of using aircraft as a means of safeguarding the shores of New Zealand. Both Hood and Moncrieff, along with others involved in the flight, had served during World War One, and through these experiences, had a belief that the navy and land defence forces would be enhanced through aviation support. Additionally, commercial benefits were also highlighted, with postal services and passenger services being mentioned as business opportunities.

The flight across the Tasman was seen as a step in proving these theories. Both New Zealand and Australian Governments were aware of the proposed flight, with the Prime Minister, the Hon. JG Coates being sympathetic to the proposal, but not committing any funding. The Australian position was distinctly different; a statement published in September 1927: “Action to prevent attempts at long overseas flights in machines which are not suitable for the purpose will be immediately taken by the Federal Ministry. The tragedies which have occurred in other parts of the world have been considered by the Ministry, and it has been decided that in future no aircraft, except seaplanes, flying boats or amphibians, will be allowed to be used in flights over a longer distance than 50 miles in a direct line from coast to coast." As a result of this, Coates wrote to his Australian counterpart, Rt Hon. Stanley Bruce, and after a 10-day wait for the response, it was clarified that the attempt would be discouraged unless the aircraft was a seaplane, flying boat or amphibian.

Just before these discussions, and as part of the preparations for the flight, a trust (the Tasman Flight Fund) was established to raise funds and manage the money. The scheme was the brainchild of John Moncrieff. He approached Captain Ivan Kight, a Dannevirke lawyer, who he knew because they were both in the New Zealand Air Force Reserve, and Kight, along with Moncrieff's uncle, Mr J. McRorie of Dunedin, each contributed £500. Kight did further fundraising, bringing the total up to about £3300. This was enough to buy the aeroplane, freight the aircraft to Australia, travel to Australia, and spend time making the necessary adjustments before attempting the flight.

When Hood, Moncrieff, and Kight bought the aeroplane, the Ryan’s interior was upholstered in silk mohair. Deep cushioned chairs lent comfort, and a thick lining of balsam wood between fabric and upholstering minimised engine and propeller noises. While in Australia, the aircraft was modified before the flight on 10 January 1928. The four passenger seats were taken out, to make room for an extra fuel tank and to bring the weight of the aircraft down to a minimum, and a special seat was installed instead for the second pilot, John Hood. The plan was that the four seats were to be sent to Wellington to be refitted after the flight had been completed.

In the days leading up to the flight, Kight, Hood, and Moncrieff completed a training run over Bong Bong, a small township in New South Wales. For this flight, they used only the aircraft compass for navigation. During this trial, it was noted the wireless had failed to perform, however, this was, seemingly, of small concern. It was also in late December that Rt. Hon. Bruce withdrew the orders which prohibited the flight, and this was of great relief to those involved.

The seat MOTAT has in its collection is catalogued as ‘Wicker Chair [Aircraft chair ex Ryan G AUNZ 'Aotearoa']’ and has the accession number 1964.238. It is one of the four wicker seats removed from the aircraft before the flight. This was done to reduce the weight of the plane. The seat is made from wicker cane and has no arms. It has a high, arched backrest. The two rear legs are shorter than those at the front, giving the chair a backward slant. There are cross-member cane rods under the chair and between the legs to give the chair rigidity.

The second seat is the very same in make and finish, however, its condition is showing wear and tear, and there are areas of loss – including the silver plaque. This chair has the accession number 1981.502. Recently it has been identified as being from the Estate of Mr GPH Davidson, and it was presented to MOTAT in early 1974 by representatives from the National Airways Corporation (NAC). The MOTAT Museum News references this gift as being a ‘Wicker chair from the Ryan Brougham monoplane of Hood and Moncrieff’.

After the failed flight, a fund for the families of the two dead pilots was established and McMahon Motors in Wellington offered to recondition the four seats so that the trustees could sell them by auction – one in each of the four main centres in New Zealand – to raise money for it. Silver plates made by Wellington jewellers and silversmiths, Mayer & Kean Ltd were added to each of the chairs. The plates were inscribed: "From Aotea-Roa the first aeroplane to attempt to fly the Tasman 10th January 1928." One of the chairs in MOTAT’s collection still has the plate on the backrest.

The trustees had expected to receive all four of the seats, but only two arrived. They were to be auctioned in Auckland and Wellington on Saturday 4 February after having been on display in the window of the New Zealand Sports Service in Wellington’s Willis Street. "They are solidly built-in heavy cane work and are very neat in design. It is hoped that the sale will bring in quite a fair sum in aid of a worthy cause."

There was some confusion over who had won the auction in Wellington, and so the trust decided to re-auction the chair on 9 February. A street collection for the Moncrieff-Hood Fund was held in Wellington the next day, Friday 10 February. For some reason, the chair was again not sold by auction – and at the end of March 1928, it was ‘bought’ for £238, the total of bids by various wool buyers and brokers at a wool auction. This money was donated to the fund but the chair was not allocated to anyone. Donations continued to be received until the beginning of April when the Wellington mayor, George Troup announced that he was closing the fund. It is clear from newspaper reports that the second chair had not been sent to Auckland and that no one had bought it. It is unclear what happened to either of the chairs after the mayor closed the fundraising for the fund, but it is possible that they were given to Ivan Kight.

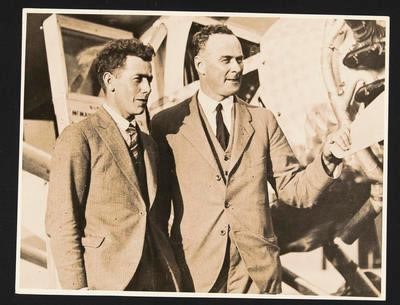

George Hood, 1893-1928 was of a Wairarapa settler family. He enlisted with the Main Body of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force and left New Zealand in 1914 as a sergeant in 9 Squadron of the Wellington Mounted Rifles. He served throughout the Gallipoli campaign and after the evacuation was posted to France. He was always interested in aviation and toward the end of 1916 was drafted as a recruit into the Royal Air Force. He qualified in 1917, but while taking up a new aeroplane on a trial flight at Lincoln his engine failed and he nosedived from a height of 2000 feet. As a result of the injuries he received, Hood lost his right leg below the knee. After some months in hospital in England, he returned to New Zealand, but then went back to the United Kingdom to continue his training. Despite the physical disability of an artificial leg, he saw service as a pilot before coming back to New Zealand, where he was placed on the New Zealand Air Force reserve with the rank of captain.

Hood attended the officers' refresher course at the Wigram Aerodrome each year after his return to New Zealand. He had made several successful experimental flights, including a flight over the Southern Alps, before attempting the flight across the Tasman.

Ivan Kight, 1896-1931 was a barrister and solicitor practising in Dannevirke. He was educated at Napier Boys' High School, before attending Auckland University College where he completed his law professional examination at the early age of 19. He left for the United Kingdom when war was declared in 1914 and enlisted as an airman. He served in England and France. On his return to New Zealand after the war, Kight maintained his interest in aviation. Like Hood, he was placed on the reserve of the New Zealand Air Force and attended an annual refresher course at Sockburn aerodrome.

He died on 8 February 1931 when the Dominion Airlines Desoutter II, ZK-ACA which he was flying from Gisborne to Hastings crashed, killing all three on board. Kight was one of the directors of Dominion Airlines.

Kight’s involvement with Dominion Airlines may explain how George Bolt acquired one of the chairs from Aotearoa. Bolt was the usual pilot for Dominion Airlines and had been flying long hours in the aftermath of the Napier earthquake on 3 February 1931, maintaining communication between Gisborne and the outside world. It is possible – even likely – that the two chairs had ended up with Kight after the fundraising for Hood and Moncrieff’s families ended, and that Bolt and Davidson then acquired one of these each after Kight’s death.

John Moncrieff, 1899-1928 was a New Zealander by adoption. Born in Scotland in 1899, he came to New Zealand at the age of 16 and trained as a motor engineer at the ABC Garage in Wellington, later joining the infant New Zealand Air Force. He was rejected for active service flying in the First World War on account of his youth, but he joined an infantry unit in the later stages of the war and from there contrived to be transferred to the Royal Air Force in December 1917, with which he served in France. On his return to New Zealand in 1919 he was, like Hood and Kight, posted to the New Zealand Air Force Reserve, and it was here that the three men met. Moncrieff also attended annual refresher courses with the Air Force Reserve and was recognised as an expert on aircraft engines. He returned to work at ABC Garage after the war.

Significance

Developments in aircraft design and capability in the 1920s meant that they became more reliable and capable of longer flights. Possibilities for passenger transport were obvious, as was the fact that air travel would be important for New Zealand because of its geographical remoteness. Ivan Kight had told newspaper reporters that one of the reasons he and John Moncrieff first became interested in a trans-Tasman flight was to highlight the importance of air defence, but ultimately it is civilian holiday and business travel that has dominated the trans-Tasman air routes.

In 1927 Charles Lindbergh had famously flown across the Atlantic. For New Zealand pilots, the Tasman Sea between New Zealand and Australia was a closer challenge. Aircraft had flown in stages from England to Australia, but none had crossed the Tasman in either direction. Although Hood and Moncrieff failed in their attempt, later the same year Australian Charles Kingsford Smith and his three-man crew succeeded when they landed the Southern Cross, a Fokker FVIIb/3m tri-motor, at Wigram, Christchurch on 11 September 1928. They had previously been the first to fly across the Pacific from California to Queensland in July that year.

Guy Menzies completed the first solo Tasman crossing in a single-engine Avro Avian bi-plane in 1931.

These flying feats were popular with the public. The number of people who waited for Hood and Moncrieff at Trentham racecourse demonstrates this, as does the crowd of 30,000 which greeted the Southern Cross when it arrived in Christchurch. The event was filmed and broadcast live over the radio so that people in other towns and cities were able to share in the excitement.

The Aotearoa was also the first aircraft to go missing in or near New Zealand. While other aircraft had crashed, until Moncrieff and Hood's flight, none were lost without a trace. In 1931 the Masterton aerodrome was renamed Hood Aerodrome, the name it still bears today, and several streets throughout New Zealand are named 'Moncrieff' or 'Hood' as memorials to the pair.

However, the most significant thing about these two chairs is that they are all that remains of this first attempt to fly between Australia and New Zealand.

Story by Belinda Nevin, Curatorial Research Manager, MOTAT and Megan Hutching, Oral Historian, MOTAT.

Citation:

Nevin, Belinda and Hutching, Megan, 2022. MOTAT Museum of Transport and Technology. Published: 7 July 2022. URL: https://www.motat.nz/collections-and-stories/stories/g-aunz-aotearoa-the-remaining-pieces-of-an-aircraft