Conserving Richard Pearse's Utility Plane

Conservator Kasserine Ross-Sheppard during conservation treatment in 2023

Conserving an icon

Much work has been happening behind the scenes in preparation for Te Puawānanga, MOTAT’s new science and technology centre, which opens in mid-2024. One of the large-scale collection items visitors will see is Richard Pearse’s Utility Plane, a prototype convertiplane invented between the 1930s and 1950s. To ensure this large and unique item is displayed safely, the Utility Plane has been the focus of several conservation treatments.

The George Bolt connection

Pearse’s Utility Plane was a multi-decade invention (1930s–1950s) and likely incorporated materials he had at hand in his Woolston, Christchurch, garage and workshop—lengths of wood, wire, steel tube and pipe, leather straps/belts, rubber parts, cotton oatmeal or flour bags. Over the years, Pearse researched, designed, made, and developed his vision of an advanced concept aircraft - a convertiplane or a hybrid helicopter-airplane with his goal of an aircraft that could take off and land anywhere, independent of aerodromes or runways, and be available to the public to buy and fly.

The aircraft has a hinged tail section and wings, as well as a tilting engine and propeller unit, which enables it to be folded up to fit inside a motorcar garage of a domestic house. All this work took place in Pearse’s garage and workshop on his Woolston property; this being one of the three houses he’d built while living in Christchurch.

By the 1930s, the idea of an aeroplane that could convert between vertical to horizontal flight, and hover, was not new or unique to Pearse; other dreamers having fancied or imagined, conceived and patented various contraptions in earlier decades. Few would be built and few could achieve anything of the seemingly impossible idea. Survivors from that daring and experimental age are hard to find.

Richard Pearse’s Utility plane outside MOTAT’s Pump House. Pearse No 3 airplane, unrestored, outside Pumphouse, 11-1165. Walsh Memorial Library, The Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT).

After Pearse’s death in July 1953, his estate was wound up, with the Utility Plane described in a newspaper report as the “wings and part of an improved autogiro” sold to the Canterbury Aero Club, where it was stored folded up in the Club’s Hangar at Harewood. It was later in this decade that New Zealand pioneer aviator, George Bolt, who had an interest in New Zealand aeronautical inventions, learned of Pearse’s Utility Plane from Captain John Malcolm, of the National Airways Corporation (NAC). The Club, having no use for it as an aircraft, offered it to Bolt, who accepted it with the intention of it becoming a feature object in a transport and technology museum then being mooted by several Auckland-based societies around this time. This entity would become known as the Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT), which opened to the public in 1964.

George Bolt at the New Zealand Flying School. P. A. Kusabs. 1910s. New Zealand Flying School, 07/080/115. Walsh Memorial Library, The Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT).

The Utility Plane’s structure (frame and fabric cover) had been compromised before it entered MOTATs collection. In a letter dated 5 February 1959, Bolt mentioned an arrangement with the Royal New Zealand Air Force’s Hobsonville training centre that could “straighten the old aeroplane up, and recondition it a bit”. There is no record of this work taking place or not while at Hobsonville, and early photographs of the Utility Plane at MOTAT show it on display in what appears to be an unrestored state.

1970s restoration project

Initially the Utility Plane was housed in MOTAT’s Western Springs Pump House Boiler Room, one of the large, covered areas available at MOTAT in its early days of operation. And, although undercover, the need to repair and restore it was apparent, and in the early 1970s this work would be championed by Sir Geoffrey Roberts, the head of Air New Zealand, in advance of the International Air Transport Association (IATA) annual conference to be held in Auckland in November 1973.

Sir Geoffrey and Lady Roberts, 1975. Portraits: Sir Geoffrey and Lady Roberts, 04-2235. Walsh Memorial Library, The Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT)

On 25th June 1973, Roberts wrote to Mr Willetts, the training manager at Air New Zealand, noting the aircraft “presents a far from satisfactory visual impression”. A month later, in July 1973, Roberts called a meeting to discuss a “course of action” for the restoration of the aircraft. Pearse’s work in aircraft design and his innovative ideas would be recognised at the IATA conference, where attendees would be gifted a sterling silver or bronze medallion commemorating Pearse’s engineering and aviation innovations. Roberts believed “it is important, therefore, that the aircraft should be restored before that meeting takes place”.

The International Air Transport Association conference medal commemorating Richard Pearse. Waitangi Mint et al. 1973. Medal [Commemorative], 2001.93. The Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT).

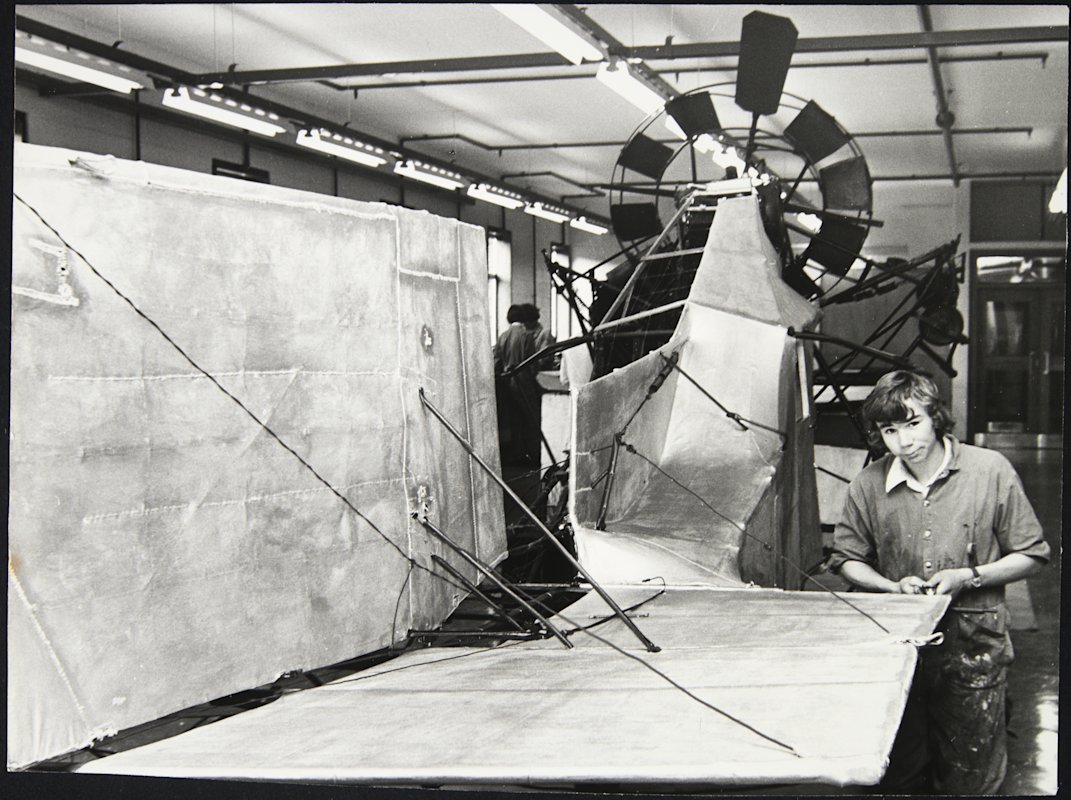

Soon after Robert’s restoration meeting, the Air New Zealand Training School students committed themselves to the work. Under the supervision of Bill Harold, an Air New Zealand aviation engineer and training school instructor, the restoration became a three-month project for the airline’s engineer apprentices. During this restoration, the two-cylinder 60hp engine was cleaned (and showed provision for 24 spark plugs), metalwork repaired, wooden struts patched, and the original fabric covers – oatmeal bags – were removed and replaced with unbleached calico. Half of the aircraft was covered in the fabric (and painted metallic silver) and supported by stainless-steel wire, with the other half being left uncovered, exposing the internal structure.

An apprentice from the Air New Zealand engineering school during the 1973 restoration project. 1973. Pearse No 3 Airplane : an apprentice restoring the airplane, 02-1306. Walsh Memorial Library, The Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT).

The Utility Plane received an excited reception from many IATA delegates, with comments on the “inventiveness of Richard Pearse” mentioned in MOTAT’s December 1973 Museum News report on the conference. Following exhibition at the IATA meeting, it was displayed in MOTAT’s Aviation Pavilion, which was a large building adjacent to the Western Springs Pump House and where MOTAT’s aircraft were displayed for visitors to enjoy. Additional aviation displays were housed in an ex-Army Nissen Hut flanking the Aviation Pavilion.

Both buildings soon became too small for MOTAT’s aircraft collection and a new display building was planned. The Pioneers of Aviation building, which included an exhibition area with a mezzanine and the Walsh Memorial Library, was opened in April 1977. Here, the Utility Plane became a centerpiece in the exhibit. This display was refreshed in the early 2000s, with conservation cleaning completed on the aircraft in 2003. The aircraft was displayed in a workshop setting—complete with tools, materials and a workbench, evoking Pearse’s inventing years. The Utility Plane was removed from this display in mid-2014, when the building was closed for improvements, and was given a well-deserved rest in MOTAT’s secure Collection storage unit.

Preparing for Te Puawānanga Science and Technology Centre

The Utility Plane was identified for inclusion and display when planning for Te Puawānanga started in mid-2022. This early commitment to the aircraft, with its corresponding comprehensive conservation assessment completed in 2023, identified two distinct treatment applications.

The airframe was the first area for conservation work, starting with identification of various of materials, components and mechanisms used by Pearse, and then during the 1973 restoration, and an assessment of the condition of each individual part was completed. The Utility Plane has unpainted and painted metal surfaces; each resulting in different condition outcomes. The unpainted surfaces showed corrosion, discolouration and a rough surface, while the painted surfaces had corroded top surfaces, paint losses and delamination. The soiled wooden parts of the aircraft, while mostly structurally sound, had evidence of an earlier repair to one wooden strut (it is unclear if this was Richard Pearse‘s work, or Air New Zealand’s restoration) and damage to another wooden strut that was of deep concern to our conservators and structural engineer. The 1973-era fabric also showed signs of wear and tear, with rips mostly caused by the corroding metal frame and surface soiling. Rubber and leather materials also showed signs of deterioration or damage.

Following this assessment of materials, a treatment plan was developed that would align any work undertaken in 2023 to the 1973 restoration. The stabilisation of the metal areas and preservation of as much of the existing paintwork as possible, were prioritised. Degreasing was completed on all the metal areas, and tannic acid was applied to the unpainted steel surfaces, including the tubular framing, pulleys, wheel components and the tail rotor. Microcrystalline wax was applied to all accessible unpainted and red-painted metal surfaces, which acts as a preventative measure against metal corrosion. The silver-painted metal surfaces were stabilised with a rust-inhibiting paint. Wooden surfaces were wet cleaned with a diluted non-ionic surfactant.

Detail of treated fuselage with several museum identification tags dated from the 1970s, early 2000s and now.

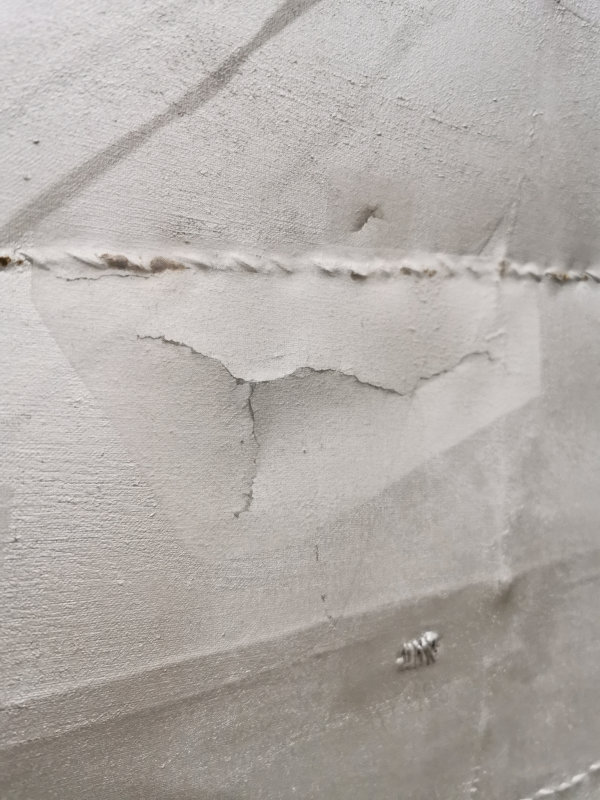

With the wood and metal areas stabilised, the second treatment area, the 1973-era calico covering, was tackled. An initial assessment determined much of the covering was structurally sound but contained cracks, tears and punctures in the fabric. The silver-coloured paint coating left the fabric brittle and stiff, which discounted any stitched repairs from happening. Instead, an adhesive patching method was developed to both provide the support necessary for display, and to visually reintegrate the tears, making them less noticeable. As there was no access to the back of the calico, the adhesive patches were applied to the surface, meaning the support material selected would need to be a good visual match for the silver coating. After surface cleaning the covering with a diluted non-ionic surfactant, a series of small test patches of support material were applied. Small patches of Japanese tissue, non-woven polyester, and silk organza were applied to tears with a water-soluble acrylic adhesive. Once dry, each patch material was evaluated for both its visual appearance and how well it adhered to the uneven surface of the calico. Silk organza was determined to be the best option as it conformed well to the uneven surface, and its natural lustre was sympathetic to the silver coating.

Conservator Karin Konold applying a silk organaza patch to a tear in the fabric covering on the Pearse Plane.

However, the loose, open weave of the silk organza proved difficult to handle as it would quickly distort during application, making it tricky to align the patch’s weave with that of the calico covering. To solve this problem, strips of organza were pre-coated with highly diluted acrylic adhesive and allowed to dry, resulting in a slightly stiffened fabric that was easy to cut into shape for each patch and did not distort. When cutting the patches to fit each tear, care was taken to keep the weft of the silk organza aligned to the weave of the calico around the tear. A mis-aligned patch could catch the light differently to those around it, causing it to stand out. Using a standardised weave direction would help create a more visually cohesive result.

The finished patch on a tear on the vertical part of the aircraft tail.

Conservation results and next steps

These focused conservation treatments have stabilised the various metal and wood components that make up the Utility Plane, preserved the existing paint layers, as well as stabilised the fabric covering. Further repair was identified during these treatments: the wooden wing struts (which hold up the wings) required a structurally sound substitute to ensure safe display, and metal struts have been made for this. In addition to the physical stabilisation, documentation in relation to the conservation treatments were added to MOTAT’s collection records and these will be used to inform any required future treatments. Ongoing collection care, inspection and maintenance within Te Puawānanga will be regularly scheduled, and we’re excited to be showcasing this unique item from MOTAT’s collection.

The Pearse Utility Plane will be transported and installed in the coming months. Another article will detail more behind-the-scenes work to get the Pearse Utility Plane on show!

AUTHORS: Kasserine Ross-Sheppard, Liz Yuda and Belinda Nevin.

EDITORS: Chelsea Renshaw, Karin Konold and Philip Heath.

THANKS TO: Roland Brownlee for archival support and Philip Heath for additions.

Sources:

Heath, Philip, "A Private Plane for the Million". Richard William Pearse’s Convertible Aeroplane-Helicopter 1933-1953, 2013

MOTAT collection files, Richard Pearse, "Whether he beat the Wright bros or not … Wizard of Waitohi will keep date with history – Thanks to this." n.d.

MOTAT, Walsh Memorial Library and Archives, Manuscript, MSS-0191.1.6, George Bolt. 1956-1960. [George Bolt correspondence regarding Richard Pearse]

Museum of Transport and Technology, Museum News, December 1973

Stone, Harold (compiler), "The Museum Makers", Otamatea Kauri & Pioneer Museum Trust Board, Matakohi, 1996

Yuda, Liz, "Pearse Utility Plane report from 6 June 2023", 2023

Article published April 2024