Best Reached by Rail: Special Occasions

This blog was written by guest author Neill Atkinson

The 1920s and 1930s were a pivotal era in the democratisation of family holidaymaking in New Zealand. During these years the state-owned New Zealand Railways (NZR) – and its emerging publicity and advertising machine — helped to propel a boom in domestic tourism by using sophisticated, aspirational marketing to appeal to holiday consumers, especially families.

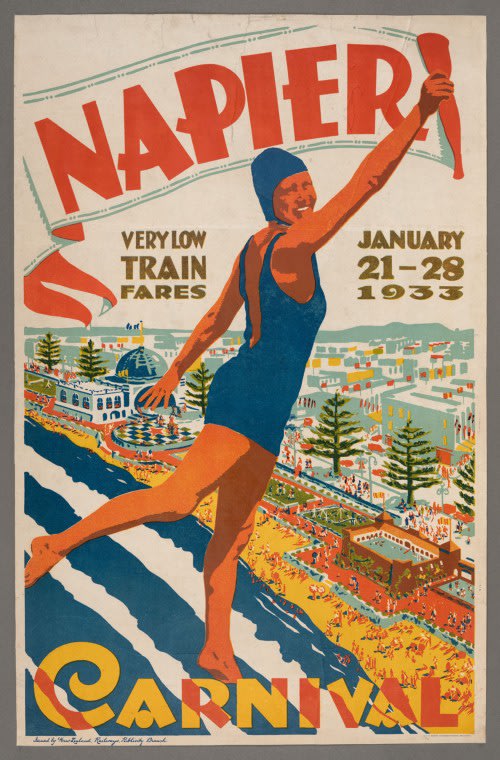

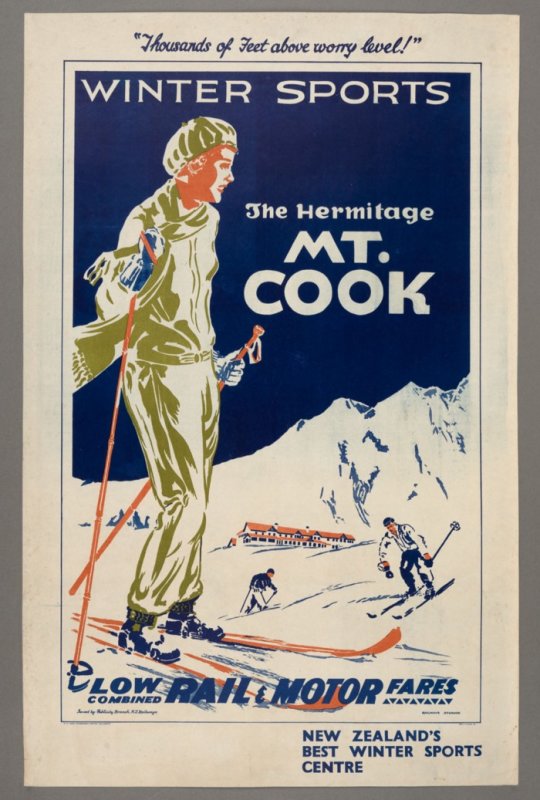

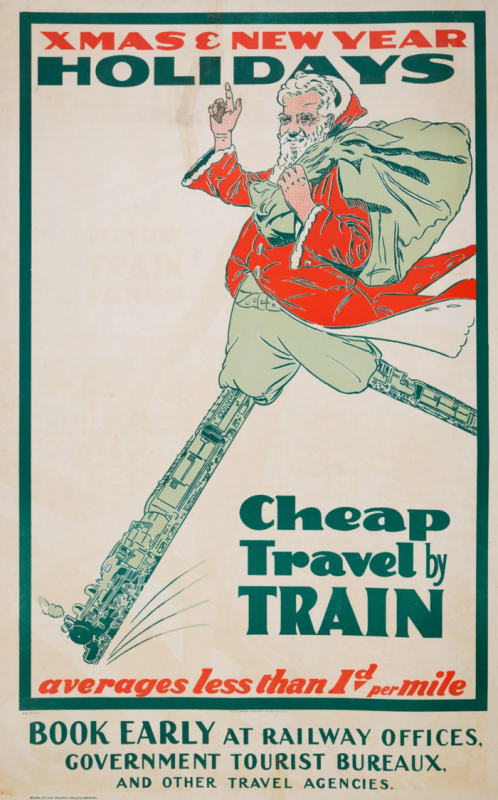

Central to this effort were the striking advertising posters and billboards produced by the Railways Studios, which enticed prospective travellers with images of golden, sun-drenched beaches, soaring mountains and lush forests, Santa Claus and Easter eggs, and symbolic figures like the ‘bathing belle’ or ‘seaside girl’ (as seen in the Napier Carnival poster). The interwar expansion of tourist rail travel, particularly to coastal settlements in the summer months but also to alpine destinations and thermal attractions, helped set new fashions, change social patterns and carve out new leisure spaces.

While there has been relatively little research into the origins of domestic tourism in this country, most New Zealand historians agree that, as in Britain, the United States, Australia and other similar societies, the interwar decades saw a significant democratisation and diversification of consumption, including the consumption of travel, recreation and family activities. Here, the rise of the family holiday has typically been associated with the interwar boom in motoring, and with local institutions like the motor camp and caravan park. Historian James Belich assumed that ‘the prerequisites of the classic Kiwi holiday away from home included the paid holiday period or one or two weeks and of the motorcar,’[1] both of which, he claimed, were widely available to middle-class New Zealanders from the mid-1920s and to the working class in the late 1930s and 1940s.

This focus on automobiles is not unique to New Zealand. ‘Obviously,’ as British historian Colin Divall noted, ‘motoring represented the “shock of the new”, and attracts historians for that reason.’[2] Similarly, while Richard White emphasised rail’s role in ‘making the Australian holiday’ prior to the First World War, in exploring the interwar decades (and post-Second World War holiday heyday) his attention switched to the ‘car revolution’ and the ‘new individualism’ it fostered.[3]

There is no doubt that New Zealanders, like Americans, Canadians and Australians, were among the world’s most enthusiastic early adopters of automobiles, and that intrepid motorists accessed remote beaches, lakes, rivers and mountain valleys from the 1920s. But many roads were rudimentary, and contemporary vehicles offered limited comfort, endurance and reliability. Better suited to short day trips, the automobile was not yet the mass people mover it would become after the Second World War. Instead, the democratisation of family holidaymaking in interwar New Zealand would be driven not so much by the relative novelty of private motoring but by the flourishing — and skilful promotion — of an existing form of public transport: railways.

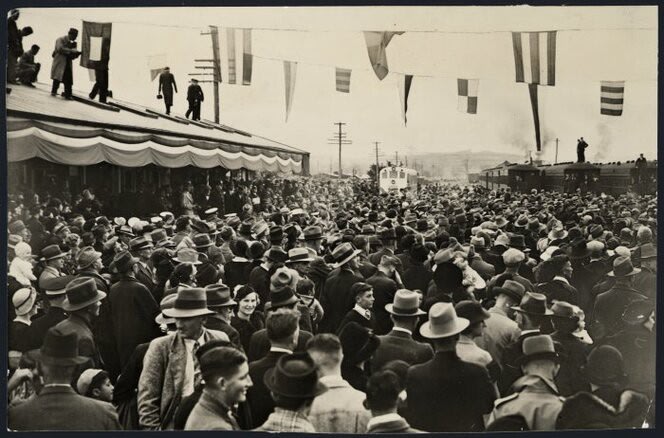

As elsewhere in the world, railways and pleasure travel had shared a long history. Early lines were built to carry freight, connecting ports, mines, forests and farming districts, but from the 1870s NZR ran regular excursions carrying picnickers, ‘pleasure parties’ and spectators to beaches, showgrounds, racecourses, sporting events and other special occasions (including lavish celebrations marking the opening of new rail lines). Day excursions were initially more popular than longer trips, however, as paid holidays were rare and few people could afford the cost of overnight accommodation, even if it were available.

That began to change in the interwar decades, when a number of factors coalesced to create fertile conditions for a domestic tourism boom. The physical leisure culture that had emerged in the late 19th century flourished in the years after the First World War, convincing ever more people of the recuperative benefits of fresh air and outdoor recreation. Declining family sizes made longer holidays a cheaper and more manageable option. Wages were generally rising, especially for clerical and skilled blue-collar workers, and working hours declining.

The majority of office and factory workers were now entitled to paid annual holidays of a week or a fortnight, not as a statutory right — the first legislation providing for annual paid holidays, a minimum of two weeks, was passed in 1944 — but through industrial awards and agreements covering large sections of New Zealand’s heavily unionised workforce (including railway workers, who enjoyed additional benefits such as discounted travel).

By 1928 paid annual leave was so widely established that the Railways Magazine could proclaim that February — rather than the Christmas–New Year period or Easter, when workers could take advantage of statutory public holidays — was ‘of all months in the year, the favourite for holiday travel in New Zealand’.[4]

Governments of all political stripes sought to foster domestic tourism. As historian Erik Olssen has observed, the Reform government of the 1920s championed a ‘society of land and home owners, blessed with ample wages and holidays, enjoying the fruits of prosperity, travelling to the nation’s scenic resorts’.[5]

NZR’s Publicity and Advertising Branches, including the skilled artists of the Railways Studios, led by Stanley Davis, worked closely with the Tourist Department, private tourist operators and the emerging advertising industry to generate holiday consumption, selling pleasure to generate ‘a demand not previously existent’ and ‘build up profitable new lines of business.’[6]

Although overall rail journeys predictably fell during the tough Depression years of the early 1930s, domestic tourism remained surprisingly buoyant, as travellers were lured to seaside destinations like the Bay of Islands, Tauranga and Timaru, ‘Merry Winter Sports’ at Tongariro and Mount Cook, and to special events like the Napier Carnival in January 1933 — promoted via a promise of ‘very low train fares’.

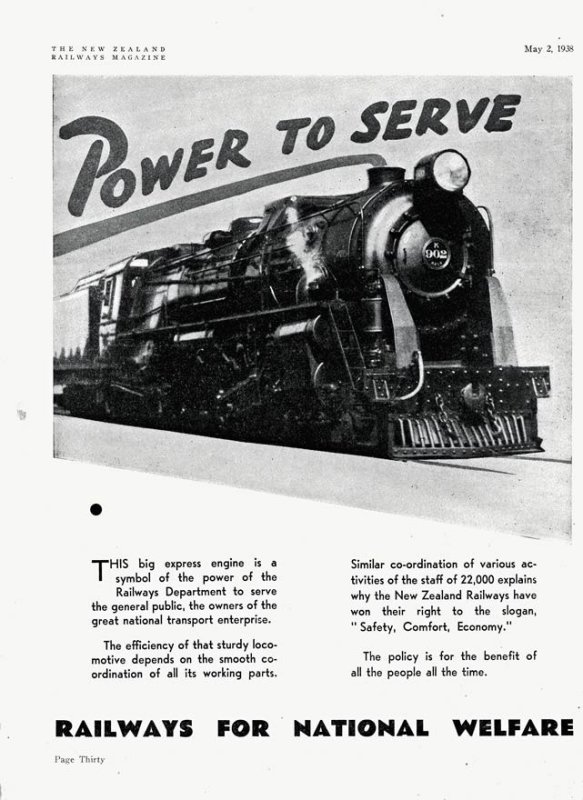

As the economy improved, the new Labour government elected in 1935 would go even further. Labour’s democratic vision for rail was articulated in advertisements championing ‘Railways for National Welfare’ and ‘The People’s Railways for the People’s Profits’.

The Minister of Public Works (and later of Railways), Bob Semple, promised to build new routes to bring ‘the natural beauties of our country … within easy reach of all of our citizens’ [7] New electric locomotives and railcars, new city stations and sleek art deco advertising imagery symbolised the glamour, power and modernity of a revitalised state rail system, connecting mobile citizens to the country’s scenic resorts.

After the low point of the early 1930s, rail passenger traffic began to revive from the summer of 1934–35, boosted by a royal visit by the Duke of Gloucester and the Studios’ expanding output of advertising posters, billboards, and print and cinema advertisements.

On Christmas Eve 1934, five trains — Night and Daylight Limited's, the regular express and two ‘relief’ expresses — carried 1,800 travellers from Wellington to Auckland; two years later, seven were needed. Over the 1937 Christmas break, more than 32,000 travellers left Wellington by train for holiday destinations around the North Island. The following year, 11,000 departed on Christmas Eve alone, crowding aboard sixteen long express trains. The New Zealand Herald captured the bustle and clamour of Auckland station at Christmas time:

Throngs of people in the most diverse kinds of holiday attire, people laden with suitcases, bags and parcels of every conceivable shape and size, and above all children, armed with buckets and spades, toy aeroplanes, squeakers and a hundred and one other toys, all hurried or were hurried down the platforms, until it seemed that everyone in Auckland was bent on leaving the city.[8]

Following the disruption of the Second World War, beach and bach culture boomed again during the prosperous 1950s and 1960s. While the Railways Studios continued to promote rail tourism (including trips to popular events like the Hastings Blossom Festival), post-war travellers increasingly followed different paths, packing themselves, their children and ‘buckets and spades’ into cars (and sometimes caravans), which offered ‘a more private and self-contained’ holiday experience.[9]

Freed from its earlier geographic dependence on the railway, democratised holidaymaking became part of what American historian Michael Kammen has termed the ‘privatisation of leisure’.[10] Tens of thousands of New Zealanders were still ‘bent on leaving the city’ in the summer months, but they would no longer crowd the public spaces of the nation’s railway carriages and station platforms as they had during the interwar golden age of rail tourism.

Neill Atkinson is Chief Historian/Manager of Heritage Content at Manatū Taonga — Ministry for Culture and Heritage, where he is responsible for the Ministry’s history and reference websites: Te Ara — Encyclopedia of NZ, Dictionary of NZ Biography, Te Tai Treaty Settlement Stories, 28th Māori Battalion and NZ History.

He is the author of six books and a number of articles and chapters, mostly on New Zealand political and transport history, including Crew Culture: New Zealand Seafarers under Sail and Steam (Te Papa Press, 2001) and Trainland: How Railways Made New Zealand (Random House, 2007).

References

[1] James Belich, Paradise Reforged: A History of the New Zealanders (Allen Lane The Penguin Press, Auckland, 2001), p. 528.

[2] Colin Divall, ‘What Happens if We Think About Railways as a Kind of Consumption? Towards a New Historiography of Transport and Citizenship in Early-Twentieth-Century Britain’, Institute of Railway Studies and Transport History, York, Working Papers (2007?), URL: http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/irs/irshome/papers/T2M%20paper.htm

[3] Richard White et al, On Holidays: A History of Getting Away in Australia (Pluto Press, North Melbourne, 2005), pp. 65–9, 96.

[4] ‘The Holiday Month’, New Zealand Railways Magazine, 1 February 1928, p. 12

[5] Erik Olssen, ‘Towards a Reassessment of W. F. Massey’, in James Watson & Lachy Paterson (eds), A Great New Zealand Prime Minister?: Reappraising William Ferguson Massey (Otago University Press, Dunedin, 2011), p. 29.

[6] NZR General Manager Garnet Mackley, in NZ Railways Magazine, 1 June 1935, p. 8.

[7] Public Works Statement, AJHR, 1936, D-1, pp. ii, xi.

[8] New Zealand Herald, 24 December 1935.

[9] White, On Holidays, p. 140.

[10] Michael Kammen, American Culture American Tastes: Social Change and the 20th Century (Basic Books, New York, 1999), p. 24