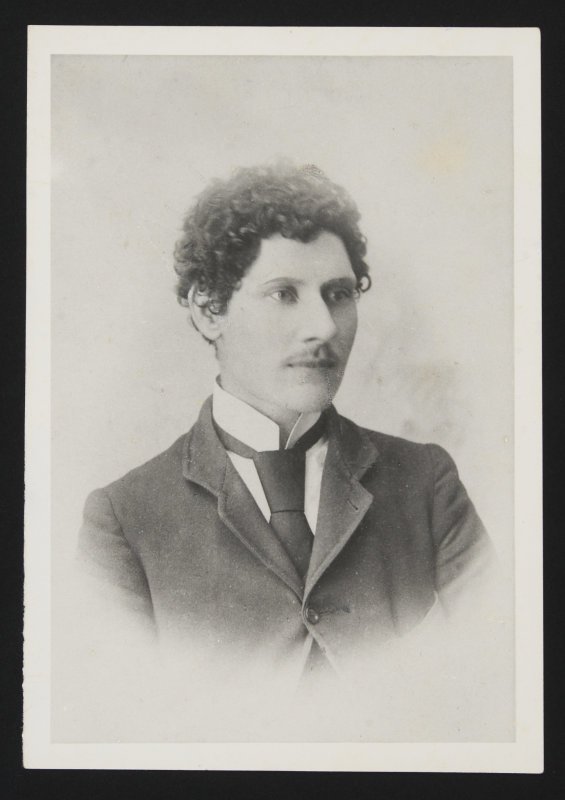

Richard Pearse and his remarkable hybrid plane

Image: Whites Aviation Limited. 1958. Richard Pearse, 15-1666. Walsh Memorial Library, The Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT).

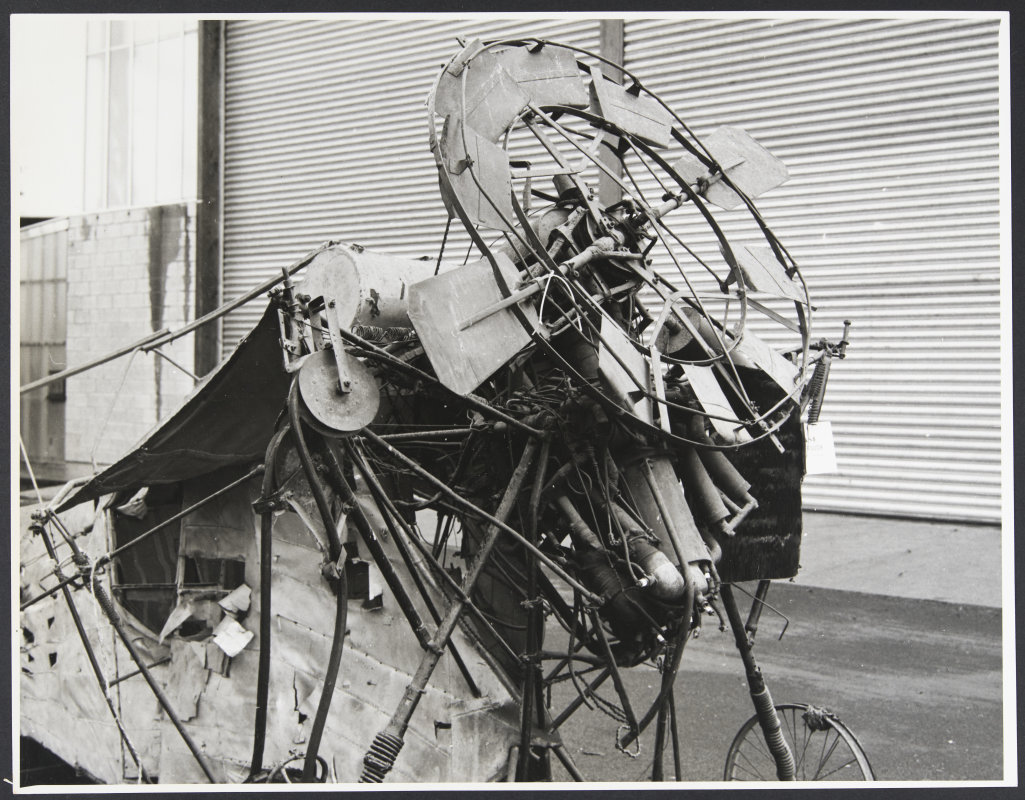

The Utility Plane

The Pearse Utility Plane is a two-seater monoplane with a hybrid propeller/rotor mounted at the front. The propeller has variable pitch, and the engine could operate as either 2-stroke or 4-stroke. It is a tubular metal structure with a light fabric covering which has been painted. The original material was removed and half of it replaced in 1973 when Air New Zealand’s engineering department restored the aircraft for display. The other half was left uncovered to show museum visitors the inner workings of the aircraft.

The aircraft has three wheels for take-off and landing – two at the front and one at the back. There are controls inside the cockpit for the engine, and foot pedals for working the rudder. The tail section is hinged and was designed to fold forward for storage.

Known as the Utility Plane, Richard Pearse’s idea behind the design was that it would be an aircraft that could land and take off from all types of terrain and could ascend and descend in restricted areas thus removing the need for landing strips or aerodromes. In other words, it was to be a hybrid aeroplane-helicopter. His design resembled a gyroplane but involved the tilting propeller/rotor and monoplane wings, which, along with the tail, could fold to allow storage in a conventional garage. The concept of a convertiplane was not new at the time when Pearse started his project, and the aeroplane model represents Pearse’s ideas on how this could be achieved.

Image: Unknown Photographer. Unknown. Richard Pearse, 15-1649. Walsh Memorial Library, The Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT).

Early interest in engineering

Richard Pearse was born in 1877 to a family of nine children, Richard being one of the middle children. Pearse’s father, Digory, had settled in New Zealand at 21 and bought a farm in Waitohi, Canterbury, South Island. Digory married Sarah Browne from County Derry, who was staying with her sister in Temuka when they met. The Pearse family kept themselves busy with farming work but also enjoyed participating in local sporting events such as tennis and golf. They had a family orchestra which Pearse played the cello in – an instrument he played and prized for the duration of his life.

Pearse displayed a knack for inventing and an active interest in engineering and mechanics from a young age, joining the local library to read periodicals with the latest updates on engineering and mechanics. He did not get the chance to go to university, as the family only had funds to send their eldest son. Despite this, Pearse maintained a lifelong interest in mechanics and engineering with a particular interest in the problem of flight. In 1909 Pearse explained that ‘From the time I was quite a little chap, I had a great fancy for engineering, and when I was still quite a young man, I conceived the idea of inventing a flying machine. [1]

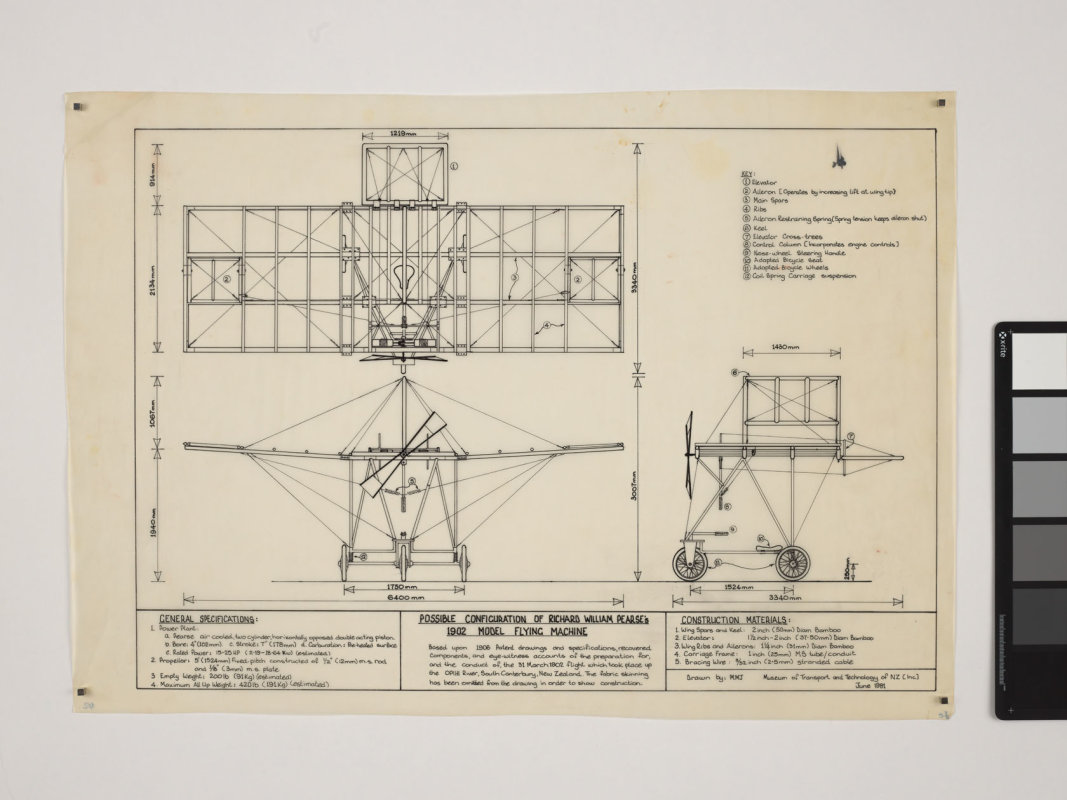

His first aircraft, which he worked on alone for many years from around 1899, was a high wing monoplane. Pearse used bamboo for the aeroplane body and tubular steel for the tricycle undercarriage which held pneumatic bicycle wheels. The machine’s engine was a 2-cylinder horizontally opposed, air-cooled radial type with a 4-inch bore. Pearse constructed components of the engine, evident from when the remains were excavated in 1971 and analysed by National Airways Corporation’s engineer and Vice President of the Aviation Historical Society of New Zealand, J. Wilton Johnston. It is known that Pearse received some help on parts fabrication by Cecil Wood, a Timaru engineer and the first person to construct an internal combustion engine in New Zealand. Wood showed Pearse how to make spark plugs and surface carburettors.

Image: MOTAT. Jun 1981. Possible Configuration of Richard William Pearse's 1902 Model Flying Machine, PLN-2020-2.3. Walsh Memorial Library, The Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT).

Groundbreaking inventions

It seems that Pearse completed the aircraft and began to carry out trials on his farm in it from 1902. At some time – it is still debated when this happened – he brought the aeroplane out onto the Main Waitohi Road where, with his brother Warne’s help and in front of some witnesses, he got it up into the air for a brief period before it veered to the left and crashed into a gorse hedge. Was this a flight or a hop in the air? It does not appear to have been very controlled or sustained so, in terms of length or control, this and other tests by Pearse at this time are probably not candidates for a true definition of flight.

Even Pearse did not claim that he was first in the world, but he did claim to have made some important and groundbreaking inventions for aeroplanes. In a letter to the Dunedin Evening Star, 10 May 1915 he wrote: "The honor of inventing the aeroplane [...] is the product of many minds [but] pre-eminence will undoubtedly be given to the Wright brothers [...] as they were actually the first to make successful flights with a motor-driven aeroplane". [2] (Orville and Wilbur Wright are credited with making the first controlled, sustained flight on 17 December 1903 near Kitty Hawk in North Carolina, USA.) Pearse’s early flight attempts were also noteworthy for powered take-off because, unlike the Wright brothers who used a launching rail, Pearse’s aircraft was able to take-off unassisted.

Image: Whites Aviation Limited. Unknown. Landscape view of the area where Pearse was active in the Upper Waitohi region of Canterbury.15-1669. Walsh Memorial Library, The Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT).

Predating the Wright brothers?

Pearse also claimed to predate the Wright brothers through his use of what he termed ailerons, or movable flaps on the wings to control the aircraft. Pearse claimed to have invented and patented ailerons (patent No. 21476, gazetted 8 August 1907). It is in the context of aviation "firsts" that Pearse wrote to the Evening Star in 1915, pointing out that his aileron patent predated that of the Wright brothers for something similar, that his tricycle undercarriage with air-filled tyres on the wheels was also the first time this had been attempted. [3]

Later interpretation by Gordon Ogilvie suggests that what Pearse had come up with was closer to "air brakes", "steering air brakes" or "spoilers", which were positioned in the place of ailerons, noting that neither draft or final patent for this aeroplane combined ‘an acceptable three-axis system to give his plane longitudinal, lateral and directional control. He may have been within an ace of achieving this, and his letters suggest that he may have actually done so but his aeroplane was too large and unwieldy to fly at a sufficient speed for the controls to be worked effectively.’

Regardless, this first aircraft of his was a remarkable invention, though, with many innovations for the time: a monoplane configuration (most aircraft at the time were bi-planes), wing flaps and rear elevator, tricycle undercarriage with steerable nosewheel (this configuration was only widely adopted during the Second World War), and a propeller with variable-pitch blades driven by a double-acting horizontally opposed petrol engine.

In 1907, Pearse began work on a second flying machine. It had huge circular wings with a 40-foot span and was unmanageable in flight, so he did not persevere with it. After a move to a farm in Milton in 1909, followed by service overseas during the First World War, then a few more years farming in Milton, he moved to Woolston in Christchurch where he built three houses, living in one and renting the others. It was in the late 1920s that he returned to his interest in flying.

Image: Spanish EAV-8B Harrier II+ "Cobra.” Source: Wikimedia Commons, CC-BY SA 2.0

Backyard project

The Utility Plane was a labour of love for Pearse, who worked on it in a garage in the back garden of his Wildberry Street house for several decades starting in around 1928-9. He became more reclusive later in his life and the Utility Plane was constructed in great secrecy. Its distinctive features include the tilting engine, the variable pitch propeller, wingtip control flaps, a folding tail, ground brake, and a sliding floor. It anticipated the main feature of the Harrier jump jet and other similar aircraft – the tilting engine, which allowed for vertical take-off and landing.

Image: Pearse No 3 airplane engine, 11-0182. Walsh Memorial Library, The Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT).

Pearse dreamed this extraordinary aircraft would become aviation's equivalent of the Model T Ford, becoming "the private plane for the million", able to be flown from one's backyard. [4] He applied for a patent in November 1943 which was finally approved in 1949. Alas, the Utility Plane never flew, and this concept model was not further developed, despite Pearse writing letters outlining his invention to several leading aircraft manufacturing companies - De Havilland Aircraft Company, United Aircraft Corporation, Bristol Aeroplane Company and Vickers-Armstrong. After this, his health deteriorated, and in 1951 he was admitted to Sunnyside Hospital. Pearse’s involvement in aviation innovation had come to an end.

Following Pearse’s death in July 1953, executors of his estate sold the Utility Plane to the Canterbury Aero Club who stored it in their Harewood hangar. When visiting the Aero Club in 1956, aviator and collector, George Bolt became aware of the aircraft and worked to bring it to Auckland before it was eventually donated to MOTAT in 1964. It was later restored by Air New Zealand's engineering apprentices over a three-month period in honour of the International Air Transport Association (IATA) annual conference being hosted in Auckland in 1973.

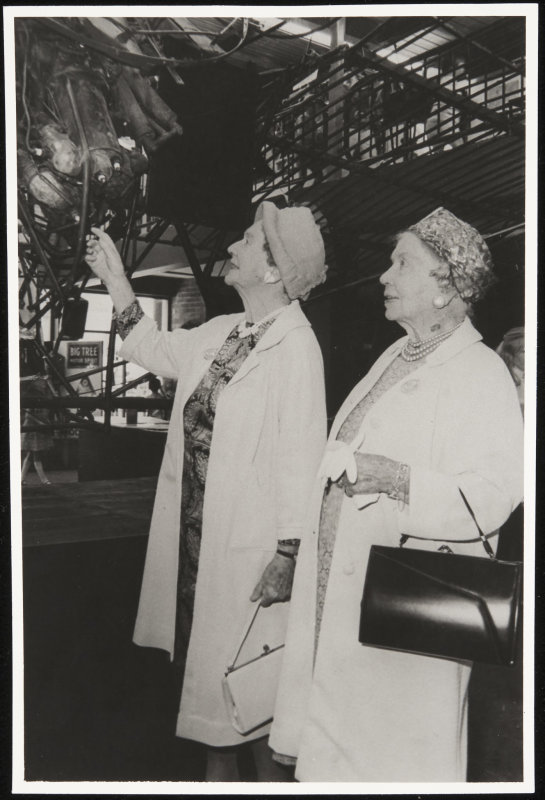

It was Bolt’s mention of the aircraft in a local paper that alerted Pearse’s surviving sisters, Ruth and Florence. They approached Bolt with information about their brother, which started the process of recognition for Pearse’s achievements in New Zealand’s history of innovation, making the surviving Utility aircraft a deserving and significant part of the story.

Image: Vahry Photography Limited. Apr 1973. Richard Pearse’s sisters Ruth Gilpin and Florence Higgins with the Utility aircraft, 15-1654. Walsh Memorial Library, The Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT).

Conclusion

Debate still rages in some circles about whether Pearse managed sustained controlled flight before the Wright brothers' successful effort in North Carolina in 1903. It is possible that Pearse may not even have known at the time that the Wrights had achieved this feat. That was not what was driving his work. Rather, he was immersed in solving the problem of flight by working out how to build a successful flying machine.

Pearse was aware of the significance of what he had achieved, as he concludes his lengthy 1915 letter to the Evening Star by writing: "As an explanation for inflicting a letter of this length on you, I may say that my object is to show that New Zealand brains anticipated the essential features of the aeroplane. If I have claimed anything unduly, I want to know it, as I am open to correction. All my experimenting in aerial navigation was pioneer work, and when a history of the pioneers is being written I hold that I am within my rights in asserting my claims." [5]

Pearse should be remembered as an inventor with extraordinary imagination and foresight whose vision far outreached the capacity of his simple workshop technology. He was nevertheless, by a wide margin (whether in 1902, 1903 or 1904), the first British subject to achieve a powered take-off in a heavier-than-air machine of his own design and construction. [6]

Pearse’s Utility Plane will be prominently displayed in Te Puawananga, our new science and technology centre opening this year. In the centre you’ll be able to see the aircraft and learn more about its inventor, Richard Pearse, along with other examples of Kiwi science and technology innovation. The centre will draw on STEAMM (science, technology, engineering, the arts, mathematics and mātauranga Māori) concepts to get curious minds sparking. The interactive nature of this space will provide plenty of opportunities to put learning into play.

Stay tuned for the next article on the Utility Plane which outlines the aircraft’s restoration history and the conservation expertise that has gone into preparing this object for display.

Co authored by Megan Hutching and Chelsea Renshaw

Published December 2023

End notes:

[1] Clutha Leader, 30 November 1909, p.6

[2] Evening Star, 10 May 1915, p.2

[3] Evening Star, 10 May 1915, p.2

[4] https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/3p19/pearse-richard-william

[5] Evening Star, 10 May 1915, p.2

[6] https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/3p19/pearse-richard-william