Going Viral: Polio and the Iron Lung

By Christen McAlpine

New Zealand has a long history of epidemics and pandemics — from the influenza epidemic that was reported by Māori in Foveaux Strait in 1817–20, to today’s COVID-19 pandemic. Protocols such as social distancing and the closure of schools and public venues has previously been seen in New Zealand’s history, affecting Kiwis throughout the early 20th Century due to a reoccurring epidemic — the Polio (poliomyletis) virus.

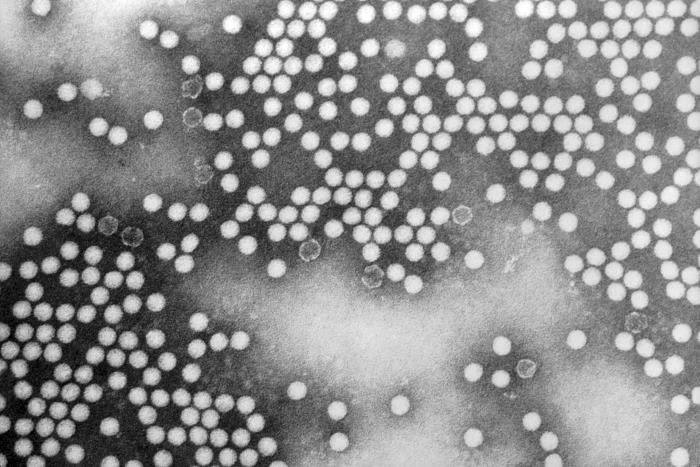

This transmission electron microscopic (TEM) image depicts numerous, round, poliovirus type-1 virions, which measured 20–30nm in diameter. Dr. Joseph J. Esposito; F. A. Murphy, 1971. CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Polio is a virus that spreads through person to person contact and can infect a person’s spinal cord. Most people who get infected will not have visible symptoms, while others will present with flu-like symptoms. A smaller proportion of the population will develop more serious symptoms such as a feeling of pins and needles in their legs (paraesthesia), meningitis or paralysis. It is this paralysis that often can lead to permanent disability and death, because the virus affects the muscles that help the person breathe. Even after recovery a small group of patients will experience post-polio syndrome.

Barbara Robin Smith, born in Dunedin in 1930, was diagnosed with polio at seven years old:

“I thought it was because I had eaten mashed parsnips, potatoes and carrots, which I loathed as a child, and I threw up at midday dinner. My Grandmother said, “she has had too much sun”. I knew I must have been ill when the Doctor came to the beach house from Dunedin to Brighton Beach and you never had the Doctor come to the house. As this was, the 1st of January 1937 and there was a very big epidemic of infantile paralysis, I guess that my Grandmother had suspicions that it wasn’t just too much sun.

I don’t remember very much after that obviously I must have had a high temperature. The first things I remember afterwards, are coming conscious of plaster casts on my legs. I was totally paralysed except for my respiratory system and it would have been months later that I remember, I was in bed with awful plaster casts that itched, and, the first time that I was taken downstairs and out onto the veranda as a treat. I also remember screaming, obviously as an adult, I realized that I had become so use to the bedroom that I had lost confidence in being taken away, a sort of cabin fever as it were.”

Polio was only recognised sporadically before 1900 but spread rapidly throughout the Western world during the first half of the 20th Century. Thousands died worldwide and many more were paralysed for life. New Zealand was not spared during this epidemic. An official report by the special committee investigating the safety of polio vaccines in 1983 recalled “epidemic poliomyelitis was the most terrifying epidemic condition in the country and the professional and public fear was justified as no specific measure of control was known.”

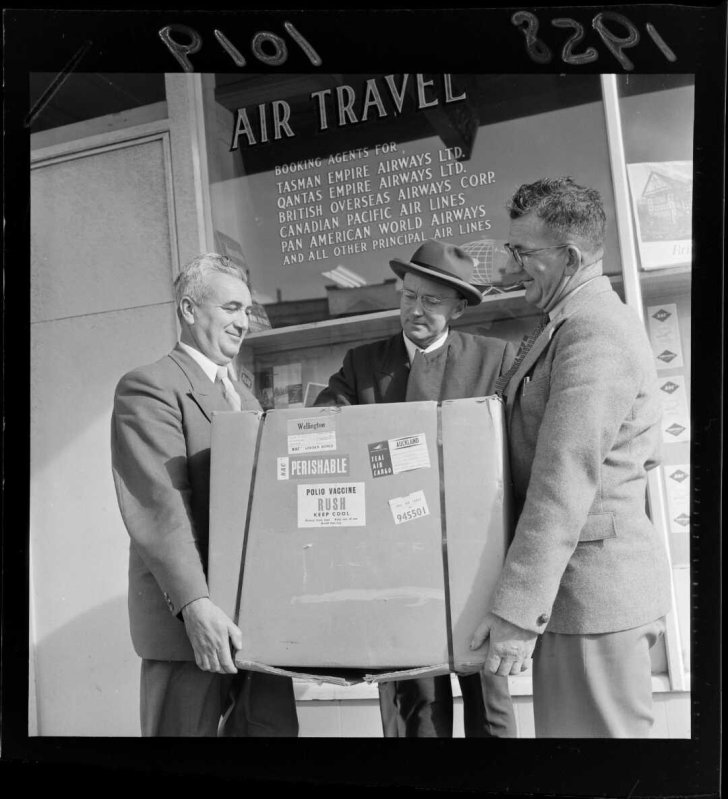

New Zealand’s first major recorded polio outbreak was in 1914 — it killed 25 people. Outbreaks occurred again in 1916, 1925, 1927, 1937, 1948–49, 1952–53 and 1955–56. Between 1915 and 1965 there were approximately 9434 reported cases of polio; of these 790 deaths occurred. The worst year for deaths from polio was in 1925, when 173 people died. It wasn’t until the introduction of a polio vaccine in 1956 that polio outbreaks started to be able to be controlled. The Ministry of Health says the last case of “wild” polio virus in New Zealand was in 1977. No cases of vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis have occurred in New Zealand since the introduction of inactivated polio vaccine in 2002. To date polio has been eradicated in every county in the world except for Nigeria, Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Three unidentified men holding a carton of Polio Vaccine, standing outside the Tasman Empire Airways Ltd office. Evening post (Newspaper. 1865–2002). Photographic negatives and prints of the Evening Post newspaper. Ref: EP/1958/1019-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

Treatments for poliomyelitis included strict bedrest and the splinting of affected limbs. Treatments were revolutionised in the 1930s by Australian Nurse Elizabeth Kenny who pioneered the use of physical therapy using hot, moist packs, massage and exercise to maximise patients’ strength in unaffected muscles enabling them to compensate for those affected.

This is similar to what Barbara Robin Smith experienced:

“The physiotherapist use to come to the house every day, for what we called massage and exercises where they rubbed my legs with olive oil and things like that. Gradually I got into a wheelchair that had my legs stuck right out in front of me and then the next thing was the calipers and crutches and then throwing away the crutches and just having the calipers. I had calipers till I was eleven when I had the first bit of orthopedic surgery done on my right ankle, which until then the foot just flopped round with a life of its own. Then I had boots that were built up, by then, I was an inch shorter on my right side. I must have improved enough to walk with built up shoes. When I was eighteen, I had another operation on the same leg and once again just walked with built up shoes. Obviously, my left side had made a remarkable recovery as my left leg carried the load of me, which has been the case for the rest of my life.”

Similarly to Covid-19, Robin was kept isolated, nursed solely by her mother and grandmother, her father allowed only at the top of the landing to shout to her, but not allowed any closer:

“It was such a big epidemic, if I was in plaster cast in hospital and I was spoon feed the custard or something like that, then I would come out in dreadful blisters under the plaster, so I was nursed at my Grandparents home which was big enough for my Grandfather and Father to be isolated in part of the house and not come near me… I do remember throwing my toy farmyard animals, when I had use of my arms, into the fire because I was so frustrated and my Uncle giving me a whack on my bottom and telling me to behave myself.”

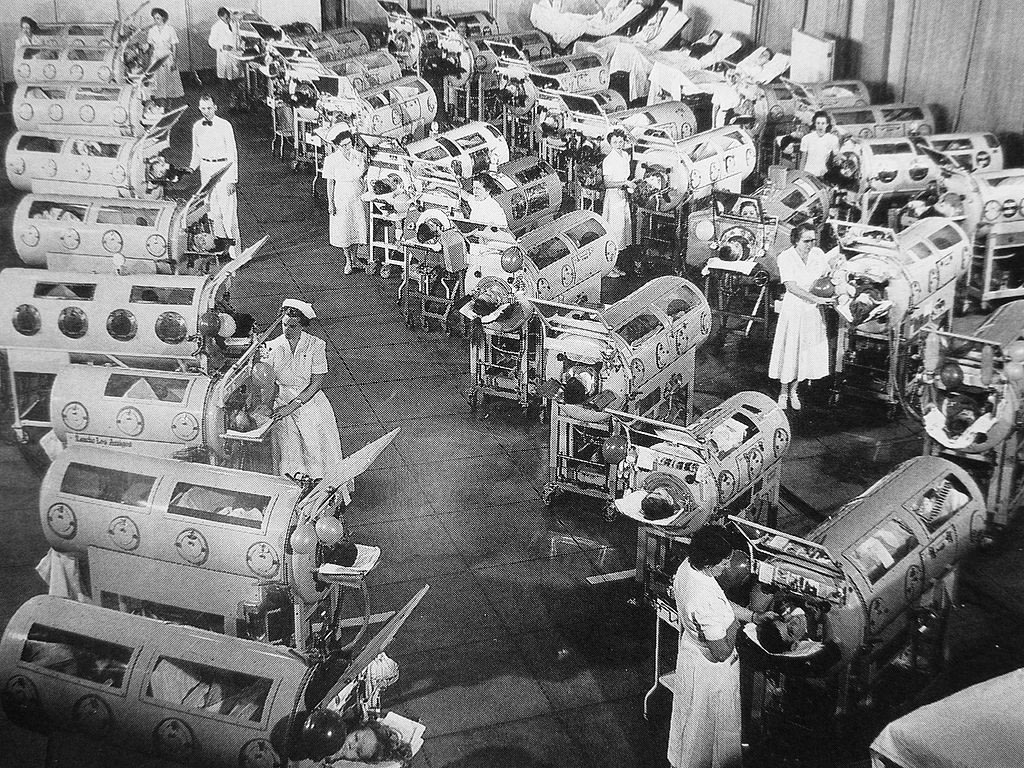

More extreme treatments during the 1910s in the USA included lumbar punctures, the internal or subcutaneous application of disinfectants like hexamethylamine or of strychnine — unsurprisingly these treatments were not effective. As the virus spread to the central nervous system, respiration could be severely impaired, and some severe cases resulted in tracheotomies to free up the airway. The use of mechanized respirators like the iron lung became a common treatment for polio related respiratory collapse.

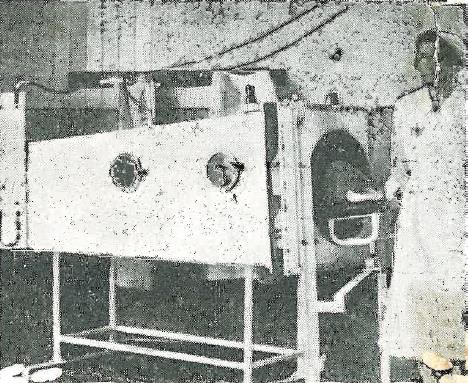

The iron lung, also known as a tank respirator, was invented in 1927 by Phillip Drinker, assistant professor in the Department for Ventilation and Illumination, and Louis Agassiz Shaw Jr., instructor of physiology, at the Harvard School of Public Health. The prototype iron lung was described as a huge metal box with a set of vacuum cleaners attached at one end to pump air in and out. The patients’ whole body was enclosed in the airtight chamber except the head which protruded from the box through a tight rubber seal to ensure air didn’t escape. The first manufactured iron lung was installed in Bellevue Hospital in New York City the same year. The Drinker Respirator still faced a variety of problems, mainly the filling of patients’ lungs with secretions, and the development of bedsores and other infections. By 1931 this design was improved by John Haven Emerson, who increased access to the patients by allowing the bed to slide in and out and by adding portholes for access to the patients inside.

Access to the patient inside during treatment could be conducted through the portholes. 1964.163. Respirator [Iron Lung], c.1935. The Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT).

The purchase and shipping of iron lungs from the USA was so restrictive, and unattainable during the depression of the 1930s, that many health departments in countries around the world turned to their own engineers to come up with cheaper alternatives. In New Zealand Fred C. Jacobs, the chief engineer for the Auckland Hospital Board, designed his version of the iron lung and had his son Bill Jacobs build it. Auckland Hospital Superintendent Dr. J.F. Caughey and Dr. J.W. Craven both consulted and supervised the project. It was built in the Auckland Hospital workshops around 1935–36 and is the first Iron Lung to have been used in New Zealand.

This end of the iron lung was opened using the handles, the patient was then put on the stretcher and then the door was sealed. The head of the patient protruded through the opening seen here (surrounded with leather). 1964.163. Respirator [Iron Lung], c.1935. The Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT).

The use of the iron lung required the patient to be put on stretcher inside of the steel welded chamber with their head protruding out of the box through a hole in the door. Once the door has been secured, a variable-speed air pump is connected to the inside of the chamber and set in motion. This pump raises and lowers the pressure of the air causing the patient’s chest, and subsequently their lungs, to be contracted and expanded for them so they can breathe. Mr Jacobs’ machine also has the capability to change the rate of the pulsations to suit the patient limits. The pump for this iron lung was a large-capacity milking plant vacuum pump that is attached to a motor with variable speed gears. The most remarkable fact about the machine is that, even with the cost of materials and labour, it was built for only £60.

The Iron Lung at Auckland Hospital. The patients head protrudes at the end where the nurse is standing. (New Zealand Truth. Man Who Should be Dead: Iron Lung Saves Life. Unknown publication date.)

Articles from New Zealand newspapers in the years following the iron lungs introduction report on the many young children, and other patients, who were sent for iron lung treatment at Auckland Hospital. One case from May of 1939 was that of Donald Nairn, a 4-year-old boy, who was suffering from paralysis due to the polio virus. Donald was rushed to Auckland Hospital from Rongotai Aerodrome (now Wellington Airport) in a Percival Vega Gull (a four-seater touring aircraft) supplied by the Wellington Aero Club since the air ambulance was undergoing maintenance. Donald was accompanied by his doctor, who administered oxygen throughout the flight, and upon landing was quickly rushed to Auckland Hospital and into the iron lung. The boy was later reported to be doing well due to his treatments. By November of 1939 the Auckland Star was reporting that Mr Jacobs’ iron lung had already been instrumental in saving five or six other patients lives in two years. The iron lung also proved useful for the treatment of unconsciousness or asphyxiation following drowning, electric shock, gas poisoning or poisoning from drugs.

New Zealand Herald, Volume LXXV, Issue 23179, 27 October 1938, Page 13

The Auckland Hospital iron lung was retired about 1950 and resided in storage at Greenlane Hospital until 1964 when the Auckland Hospital Board donated the iron lung to MOTAT. This iron lung is now a much-loved object within the MOTAT Collection and is a great example of New Zealanders innovation and the №8 wire attitude. The introduction of this machine at Auckland Hospital led to a demand for iron lungs in hospitals throughout New Zealand and contributed to the development of respiratory medicine in this country. The introduction of the iron lung is also internationally recognized as having saved many lives around the world. They are arguably one of the most recognized and significant medical apparatus of the 20th Century.

REFERENCES:

A timeline of epidemics in New Zealand, 1817–2020. Te Ara — The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Accessed: 11 May 2020. URL: https://teara.govt.nz/files/27772-enz.pdf

Auckland Star, Volume LXIX, Issue 278, 24 November 1938, Page 11. Two in Dominion: Auckland has one, Respirator Built by Public Hospital Engineer. Accessed: 14 May 2020. URL:https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AS19381124.2.81

Auckland Star, Volume LXVIII, Issue 195, 18 August 1937, Page 3. “Iron Lungs” Still Experimental. Accessed: 14 May 2020. URL: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AS19370818.2.11

Auckland Star, Volume LXX, Issue 124, 29 May 1939, Page 10.Race with Time: Paralysis Victim to Auckland by Plane. Accessed: 14 May 2020. URL: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AS19390529.2.95

Bellis, Mary. 2020. “History of the Iron Lung — Respirator.” ThoughtCo. Accessed: 13 May 2020. URL: https://www.thoughtco.com/history-of-the-iron-lung-respirator-1992009

Boating New Zealand. 2018. Reflections: Peter Jacobs, One of the Best. Accessed: 13 May 2020. URL: https://boatingnz.co.nz/reflections-peter-jacobs-one-of-the-best/

Burki, Talha Khan. 2013. When Polio Strikes. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, Volume 1, Number 5. Accessed: 15 May 2020. URL: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70155-3

Crosta, Peter. 2017. Everything You Need To Know About Polio. Medical News Today. Accessed: 12 May 2020. URL: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/155580

Global Health. “Post-polio Syndrome”. CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed: 11 May 2020. URL: https://www.cdc.gov/polio/what-is-polio/pps.html

Global Health. “What is Polio?”. CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed: 11 May 2020. URL: https://www.cdc.gov/polio/what-is-polio/index.htm

Wyatt, H. V. (2014). Before the vaccines: medical treatments of acute paralysis in the 1916 New York epidemic of poliomyelitis. The open microbiology journal, 8, 144–147. Accessed: 11 May 2020. URL: https://doi.org/10.2174/1874285801408010144

Harvard School of Public Health. 2020. Philip Drinker, polio, and that “damn machine”. Accessed: 14 May 2020. URL: https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/centennial-philip-drinker-polio/

Johnston, Martin. 2018, April 17. In New Zealand’s worst year for polio fatalities, 173 people died. NZ Herald. Accessed: 11 May 2020. URL: https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=12034351

Ministry of Health. 1983. Report to the Minister of Health of the Special Committee to Investigate the Safety of Poliomyelitis Vaccines. Government Printer: Wellington.

New Zealand Herald, Volume LXXV, Issue 23179, 27 October 1938, Page 13. Treatment not new: Several Cases in Auckland. Accessed: 14 May 2020. URL: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH19381027.2.116

New Zealand Herald, Volume LXXVI, Issue 23359, 30 May 1939, Page 8. Race For Life: Victim of Paralysis. Accessed: 14 May 2020. URL: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH19390530.2.46

New Zealand Herald, Volume LXXVI, Issue 23521, 5 December 1939, Page 10. New Iron Lung: Hospital Acquisition. Accessed: 14 May 2020. URL: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH19391205.2.88

Post-Polio Health International. Incidence Rates of Poliomyelitis in New Zealand. Accessed 11 May 2020. URL: http://www.post-polio.org/ir-newz.html.

Rice, Geoff, “Epidemics: The polio era, 1920s to 1960s. ” Te Ara- The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Accessed: 11 May 2020. URL: http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/epidemics/page-5

Ross, Jean C. 1993. A History of Poliomyelitis in New Zealand. University of Canterbury: Christchurch. Polio NZ. Accessed: 11 May 2020. URL: https://polio.org.nz/about-us/history/

Science Museum, 2018. Polio: A 20th Century Epidemic. Accessed: 13 May 2020, URL: https://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/medicine/polio-20th-century-epidemic.

Science Museum, 2018. The Iron Lung. Accessed: 13 May 2020, URL: https://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/medicine/iron-lung.

Smith, Robin. 2002. Individual experiences of wellness, illness and disability. Oral History Interview.

World Health Organisation. 2020. Does Polio still exist? Is It Curable?Accessed: 14 May 2020. URL: https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/does-polio-still-exist-is-it-curable.

New Zealand Truth. Man Who Should be Dead: Iron Lung Saves Life. Unknown publication date.

Cite this article

McAlpine, Christen. Going Viral: Polio and the Iron Lung. MOTAT Museum of Transport and Technology. First published: 22 May 2020. URL www.motat.nz/collections-and-stories/stories/Going-Viral-Polio-and-the-Iron-Lung